|

THE "DARA" DISASTER - A RECOLLECTION.

by Narve Sorensen

|

|

| B.I's "DARA" - Courtesy Narve Sorensen |

Some months ago I was studying the website of Mr. Ian Coombe of Montreal, Canada, www.mnnostalgia.com; I had got hints that a section dealt with my former employer A/S Thor Dahl of Sandefjord, Norway, and

one of its liner services, the Christensen Canadian African Lines (CCAL). Since I have been a collector of ship pictures on

behalf of this company, I came in touch with Ian and said that I maybe could help him complete his collection of CCAL vessel

pictures. I also mentioned to him that, when looking through the various parts of his website, old memories came back, especially

when seeing pictures of the SS DARA fully ablaze in the Persian Gulf in 1961, a disaster of which I played a small part in

the rescue operations. Ian asked me if I could compile a small story in my own words, which is what I shall try to accomplish.

So here is my story.

Some 45 years ago, I was working as a Radio Officer on board the Norwegian tanker THORSHOLM.

She was a 1954 built vessel of 18840 tons deadweight, callsign LFKE. Early in the morning of April 8th 1961 we were outbound,

passing Dubai in the Trucial States, fully loaded with crude oil for Far East destinations. (Dubai then belonged to the Trucial

States, and on the British withdrawal in 1971, Dubai came together with other small states in the area to create the federation

of the United Arab Emirates, U.A.E).

At 0200 we had strong northerly gale with rainshowers and thunderstorms,

moderating an hour later with increased visibility. At 0420 the officer on duty observed a vessel on fire ahead on starboard

side some 7 nautical miles away. (I later heard that the official report said that an explosion and subsequent fire broke

out at 0443; I do not know what this discrepancy in time originates, one should think we operated on the same local time.

Generally, local time in this area is UTC (formerly GMT) plus 3 hours).

I was called on duty and reported

at once on the international emergency frequency, 500 kHz. Our radio auto alarm had not been activated, this is explained

later in this story. Anyhow, one could say that we were on the right spot at the right time. The ship on fire proved to be

the British India Liner DARA, now burning fiercely amidships. DARA was accompanied by the British transport vessel, the EMPIRE

GUILLEMOT, they had left Dubai almost simultaneously. Of other vessels arriving at the disaster scene, I can remember

the tankers BRITISH ENERGY and YUYO MARU, but some other vessels also arrived at the

scene soon after.

As the dawn came we observed 5 lifeboats and some rafts near by the burning vessel. Two of the boats were empty, half filled

with water, but it was survivors in three others, one of them almost sinking. We assisted the latter one, managing to haul

it alongside and also to get all 68 persons on board, one of them with a broken leg, another a broken arm and also

badly

burnt. They received treatment in our small hospital. The two other lifeboats sighted were assisted by other vessels. At the

same time we lowered our motor lifeboat as we had seen bodies in the sea. Under command by the Chief Officer they first picked

up two men and one woman clinging to remnants of a hatch, thereafter a man floating on a piece of plank. So far we had saved

72 persons from the lifeboat and the sea.

Several people, among them many women and children, had gathered

astern on the DARA, away from the flames, and our lifeboat was directed to the wreck to assist in saving as many as possible.

When alongside two of the crew managed to enter the aft deck to handle the panic among those poor survivors and to get them

into the lifeboat. Our crew experienced some dramatic moments on this occasion; one man tried to throw a little girl into

the lifeboat from the deck, luckily he was prevented in doing it. Also, a woman fell down from the railing into the water,

one of our crew dived and got her loose from some wreckage. At last, after much struggle, we managed to transfer all 23 alive

on the poop deck over to the THORSHOLM.

So far we had rescued 95 persons, among them Captain Charles Elson and two of his officers.

I can’t remember their names, but I think it was the Chief Officer and the Chief Engineer. Captain Elson came up in

the radio station, soaked and freezing. I supported him with a pair of trousers and a shirt, for which he was very grateful.

He then told me that no radio alarm signals or radio distress signals (SOS) was sent by DARA, as the radio room was engulfed

in black smoke almost immediately and had to be abandoned. His Chief Radio Officer was ordered to try to make contact with

one of the lifeboat emergency transmitters,

but this also failed. Eventually the EMPIRE GUILLEMOT sent out the radio distress

signals, they had been quite near the DARA all morning. At that time I was already participating in the distress radio traffic.

I also dispatched a few telegrams for Captain Elson to the owners, agents and so on.

Our search and rescue

operation continued for a time, and as we did not observe any additional survivors, it was arranged for a transportation of

the survivors to a British transport vessel. (I do not remember if this was the EMPIRE GUILLEMOT or another vessel). All went

well and at noon we continued our voyage, heading for the Hormuz Strait once again. We sailed at slow speed due to heavy rain

showers, very poor visibility and the possibility of loose wreckage in the area. Some half an hour later we suddenly heard

cries for help. The weather improved after a while and we observed several dead bodies in the sea, mostly women and children,

truly a dreadful sight. Our motor lifeboat was launched once more, and we managed to find 13 alive, two of them women. They

told us that they had been in the water for some 7 hours and they were of course completely exhausted. They would surely all

have died if we not had been, again, on the right spot at the right time. On search completion we returned and again arranged

a transfer to the British transport vessel. A total of 108 survivors were rescued by THORSHOLM and her crew’s efforts

on this day - almost 45 years ago.

It was truly a very dramatic day, also a horrendous day which I never,

never will forget. I have dreamt of it many times, but as this long time has passed, not very often any more. I have later

heard that the aft part of DARA never caught fire, and was taken in tow but sank before she could be brought into Bahrain.

I often have wondered if more could have survived if they had not entered the lifeboats or flung themselves into the sea,

but stayed on deck. But this is, of course, pure speculations. As far as I know, the official number of casualties was 238.

The major part of the above story is written in accordance with my memories only, but I have had assistance from various sources

regarding the weather details, indication of time and also how many survivors there were in our different rescue operations.

Finally, let me mention that our Captain, Ragnar Tande, later was awarded the Emile Robin Legacy as an honour to his leadership

in this rescue operation.

As to myself I served 28 years in the company, both at sea and in the main office here

in Sandefjord. Later on I worked on oil platforms in the North Sea for 15 years and I am now retired since 2002.

Regards

Narve Sørensen

..........ooooooooooOOOOOOOOOOoooooooooo..........

A CADET'S FIRST TRIP WITH CLAN LINE IN 1959

Tony Thompson relates his story in a manner that will, I'm sure,

bring back many memories of voyaging around the Indian coast at that time. The sights and

smells come alive once again in this narrative that I certainly recall from my trips with Anchor Line!

It is also interesting to note the relative tonnages of the other vessels mentioned

on Tony's voyage compared with the 'box barges' of today. A testimonial to the unprecedented consumerism sweeping

our world 46 years later!

(Courtesy SHIPS MONTHLY - Aug/92)

|

|

| "CLAN MACLEAN" - Courtesy Don Chapman |

"The telegram was short and to the point. "From Cayzer Irvine. London, to Cadet A. N. Thompson.

Join CLAN MACLEAN, Vittoria Docks, Birkenhead, 11th August, 1959".

So, this was the big moment - after 12 months pre-sea training at the Warsash School of Navigation the great

day was approaching. I was about to join my first ship, to embark upon what I then saw as a lifetime at sea.

As I write, 30 years later, it is fascinating to reflect on the changes which have occurred.

My career at sea lasted only until the end of 1965, but strong and fond memories remain and with the aid of journals and diaries

I am able to recapture that first voyage as if it were only yesterday.

After a long , slow train journey from my home in Portsmouth to Birkenhead via London, Crewe and Chester

(not the most direct route I was later to discover), I finally arrived at Vittoria Docks, to find no trace of 'CLAN MACLEAN'.

I was directed to the office of the Marine Superintendent (Captain Mobbs - a most delightful man) who revealed that the ship

was not due at Birkenhead for, at least, another 7 days! Such errors in dates were common in those days, but rather

perplexing for a young first tripper standing on the quay with all his luggage and nowhere to put it!

But I need not have worried. Captain Mobbs soon found me a stand-by berth on another company ship

the 'CLAN SHAW' which was lying in Alfred Basin, Birkenhead waiting to load.

'CLAN SHAW' was the first of the streamlined "S" class of 4 vessels. Built in 1949 and of 8,100 gross

tons, she had excellent accommodation for 12 passengers and a service speed of 17 knots. 'CLAN SHAW' represented the

company at the Coronation Fleet Review in 1953, but she was to meet a sad end when as the 'SOUTH AFRICAN SEAFARER' she

stranded outside Capetown on July 1st. 1966 and became a total loss.

I spent one week aboard 'CLAN SHAW' before 'CLAN MACLEAN' arrived and I transferred to my permanent berth.

During this period I spent my days at the cadet school in the company's LiverBuildings offices and evenings discovering the

delights of Liverpool in those pre-Beatles days.

Other company ships in dock at that time were 'CLAN KEITH' (1942/7,174 grt, ex-OCEAN VERITY, lost in the

Mediterranean on November 5th. 1961, with heavy loss of life). 'CLAN MACDOUGALL' (1944/9,710 grt), 'CLAN MALCOLM'

(1957/7,326 grt), 'CLAN MACLEOD (1948/5,997 grt), also the Blue Funnel vessels 'MENELAUS' (1957/8,539 grt) and 'ACHILLES'

(1957/7,974 grt).

'CLAN MACLEAN' was built in 1947. Of 6,009 gross tons, she was one of a class of six vessels, the

first new buildings for Clan Line after the Second World War. Built by the Greenock Dockyard Company, each had a service

speed of 14.5 knots and no passenger accommodation.

For the first two days, as we negotiated the busy shipping lanes off the West Coast and Western Approaches,

the cadets stood '4 on 4 off' bridge watches, which quickly became an exhausting business. We were therefore glad

when we passed Ushant and headed down towards Cape Finnisterre and able to commence our routine day-work duties and studies.

Cadets were obliged to keep a daily journal, which we then saw as a pointless chore, and after a while,

due to lack of supervision, it was allowed to lapse. I now wish that I had been more tenacious in my writing for posterity,

but in those days we only thought of the present.

The sea was kind to me on my first experience and we were treated to glorious calm weather all the way from

Birkenhead to Port Said, a voyage of nine days. An early morning arrival at Port Said left lasting impressions of this

bustling entry port to the Suez Canal (bearing in mind that it was less than three years since the invasion of the Canal by

British and French forces).

We arrived at the same time as the American 'C3' type freighter 'STEEL AGE' (1943/8,000 grt) owned by Isthmian

Lines, and the Danish tanker 'VEGA', so we had to wait some time for our pilot. When he boarded, we steamed slowly up

the narrow channel and moored to buoys fore and aft on the starboard side of the main channel, immediately adjacent to the

lighhouse and the casino.

Although I had been warned, I was totally unprepared for the 'invasion' of the ship by the hordes of 'traders,

barbers, 'gully gully man' and others, all of whom claimed Scots ancestry and were named 'Jock MacKay'. All portable

equipment was securely locked away and cabins battened down.

We awaited in Port Said harbour until entering the Suez Canal with the midnight convoy, navigating with

the aid of a powerful searchlight mounted in the bow.

Ahead of us was the Radcliffe tanker 'LLANISHEN' (1957/20,978 grt), and astern was the Liberian freighter

'PEARL ISLAND' (1956/8,100 grt), owned by Monrovia Shipping.

Daylight presented a fascinating scene to the young first tripper. The barren desert of the east bank

contrasted sharply with the cultivated and populated west bank. Widening and dredging was in progress along the whole

length of the canal with the aid of massive American dredgers.

By 7 a.m. the sun was well up and having reached the Great Bitter Lake the whole convoy anchored to allow

the north-bound convoy to pass. Bringing up the rear of the north-bound ships was an ageing member of the Clan Line

fleet, 'CLAN MACBRAYNE' (1942/7,100 grt), an 'Ocean ' Class war time standard ship which started life as the 'OCEAN MESSENGER'.

We remained at anchor until midday before entering the southern section of the canal, clearing the southern

end into Suez Bay at 3.30 p.m.

After an interesting passage down the Red Sea, where all ships beat virtually the same path resulting in

some textbook collision avoidance situations, we arrived at the barren rocks of Aden where we were to refuel.

The 'MacL' class were 'goal posters', 445 ft in length and with a 61 ft. beam. Each set of goalposts

supported a heavy lift derrick of 80 tons SWL. They had a raked bow and typical Clan Line cruiser stern, composite midships

superstructure which, with the white upper hull strake, presented a smart and neat appearance. The short flat-topped

funnel showed off the famous company colours (black with two horizontal red bands) to best advantage.

There were three holds forward and two aft, each with hatchboard and tarpaulin covers. Each hold was served

by 5 or 10 ton SWL derricks with electric winches.

'CLAN MACLEAN' was a comfortable ship with spacious accommodation - a vast improvement on the austere facilities

of the wartime built ships that preceded her. The cadets accommodation was at the after end of the starboard upper alleyway

and had three berths with a separate study. She carried a typical complement of officers - Master, Chief Officer, Second

Officer, Third Officer, two Deck Cadets, Radio Officer, Chief Engineer, Second Engineer, Third Engineer, Fourth Engineer,

two Junior Engineers, Purser/Chief Steward and Carpenter. The deck, engine room and catering crews were Pakistani.

As was normal in those days, 'CLAN MACLEAN' had arrived in Vittoria Docks to complete loading, having already

loaded cargo at Fowey (china & ball clay) and Glasgow. On completion of loading we sailed from Birkenhead on August

21st. 1959, with a full general cargo for Ceylon & India.

For the first two days, as we negotiated the busy shipping lanes off the West Coast and Western Approaches,

the cadets stood '4 on 4 off' bridge watches, which quickly became an exhausting business. We were therefore glad

when we passed Ushant and headed down towards Cape Finnisterre and able to commence our routine day-work duties and studies.

Cadets were obliged to keep a daily journal, which we then saw as a pointless chore, and after a while,

due to lack of supervision, it was allowed to lapse. I now wish that I had been more tenacious in my writing for posterity,

but in those days we only thought of the present.

The sea was kind to me on my first experience and we were treated to glorious calm weather all the way from

Birkenhead to Port Said, a voyage of nine days. An early morning arrival at Port Said left lasting impressions of this

bustling entry port to the Suez Canal (bearing in mind that it was less than three years since the invasion of the Canal by

British and French forces).

We arrived at the same time as the American 'C3' type freighter 'STEEL AGE' (1943/8,000 grt) owned by Isthmian

Lines, and the Danish tanker 'VEGA', so we had to wait some time for our pilot. When he boarded, we steamed slowly up

the narrow channel and moored to buoys fore and aft on the starboard side of the main channel, immediately adjacent to the

lighhouse and the casino.

Although I had been warned, I was totally unprepared for the 'invasion' of the ship by the hordes of 'traders,

barbers, 'gully gully man' and others, all of whom claimed Scots ancestry and were named 'Jock MacKay'. All portable

equipment was securely locked away and cabins battened down.

We awaited in Port Said harbour until entering the Suez Canal with the midnight convoy, navigating with

the aid of a powerful searchlight mounted in the bow.

Ahead of us was the Radcliffe tanker 'LLANISHEN' (1957/20,978 grt), and astern was the Liberian freighter

'PEARL ISLAND' (1956/8,100 grt), owned by Monrovia Shipping.

Daylight presented a fascinating scene to the young first tripper. The barren desert of the east bank

contrasted sharply with the cultivated and populated west bank. Widening and dredging was in progress along the whole

length of the canal with the aid of massive American dredgers.

By 7 a.m. the sun was well up and having reached the Great Bitter Lake the whole convoy anchored to allow

the north-bound convoy to pass. Bringing up the rear of the north-bound ships was an ageing member of the Clan Line

fleet, 'CLAN MACBRAYNE' (1942/7,100 grt), an 'Ocean ' Class war time standard ship which started life as the 'OCEAN MESSENGER'.

We remained at anchor until midday before entering the southern section of the canal, clearing the southern

end into Suez Bay at 3.30 p.m.

After an interesting passage down the Red Sea, where all ships beat virtually the same path resulting in

some textbook collision avoidance situations, we arrived at the barren rocks of Aden where we were to refuel.

Our stay in Aden was short, and we were soon off again on the 7 day lonely passage across the Indian Ocean

to Trincomalee in Ceylon where we were to top up our fresh water tanks and unload a small amount of cargo.

Next came our first major port of discharge, Madras, on the east coast of India. We swung at anchor

outside Madras for a full 7 days, due to congestion, before we entered to commence unloading. This was a frustrating

business as it seemed that many other ships were given priority over us and entered harbour without delay, including passenger

ships and Indian flagged ships (Jala boats!) . I had begun to think that we had been forgotten and would be left to

rot, but I was assurred that such delays were common on the Indian Coast.

When we were finally allocated a berth we found our own 'CLAN CAMPBELL' (1943/9,545 grt), a B.P. tanker,

the 'BRITISH GUNNER' (1954/10,076 grt) , Bank Line's 'WAVEBANK' (1959/8,500 grt), Bharat Line's 'BHARATVEER' (1943/7,300 grt)

and a number of Scindia Line's 'Jala' ships already in port.

Once secured alongside, 'CLAN MACLEAN', was immediately swarming with dock labour, who commenced ripping

off hatch boards and unloading cargo at an alarming pace (they worked on 'piece' money) with seemingly little regard as to

whether it was destined for Madras or not!

We surely had our work cut out to ensure that only intended cargo was landed.

There was little regard for safety, speed was the essence. This was particularly evident during the

unloading of heavy steel channels, some of which were dropped over the side. On one occasion about 6 feet of the end

of one channel was impaled through a bridge-front porthole into the dining saloon, coming to rest about 6 inches above the

head of the Chief Officer (Mr. Rowlands), who was eating his lunch. He was not amused!.

We discharged about half our cargo in Madras, comprising heavy machinery, steel channels, caustic soda,

foam compound, oil and motor chassis.

We all worked hard in the intense heat and dust but there was some relief. Captain Harry Whitehead,

Master of 'CLAN MACLEAN', was renowned as a hard task master but he believed that his cadets should be properly educated and

he arranged, through our agents, for us to be taken on a conducted tour of Madras by car. I soon gained a lasting

impression of both the beauty and the squalor of India - a situation that seems to be little changed in the intervening years.

After 10 days in port we shook off the dirt and dust of Madras and headed north towards Calcutta, a two

day passage.

Calcutta was reached by a slow and tortuous passage up the river Hooghly, with it's constantly shifting

sand banks and severe silting problems. The passage took seven and a half hours with frequent breaks to anchor and await

tide levels over the various sand bars. We made the passage in company with Irish Shipping's 'IRISH MAPLE' (1957/6,218

grt) and Ellerman's 'CITY OF LANCASTER'(1958/4,900 grt).

On arrival in Garden Reach we locked into Kidderpore Dock (a depressing place which I was to get to know

well in the ensuing years), where we berthed alongside the British India vessel 'NARDANA' (1956/8,511 grt).

The rest of our cargo was discharged at Calcutta, during what was a most unpleasant and uncomfortable stay.

'CLAN MACLEAN' was not air-conditioned so we had to endue the heat and pungent odours at all hours of the day and night.

It was unwise to leave portholes open when cabins were unattended due to the abundance of sneak thieves, so we sweltered and

looked forward to the daily relief of the monsoon rains.

The waters of Kidderpore Dock were not noted for their purity, frequently containing the bodies of dead

animals, and worse! It was therefore a very unpopular task for the cadets, at the conclusion of discharging cargo, to

go over the side to repaint the draught marks and load lines. The load lines could usually be reached from a pontoon,

but the fore and aft draught marks were definately a bosun's chair job.

I have vivid memories of sitting suspended over the putrid waters of the dock, reliant on my colleague to

keep me airborne. (Strange how it was always the junior cadet who ended up in the bosun's chair, whilst the senior supervised

the lowering gear!). A ducking in those waters resulted in a swift trip to the hospital for a stomach pump and numerous

precautionary injections with blunt needles.

Once 'CLAN MACLEAN' was fully discharged we moved to a stand-bi berth to await our homeward cargo.

During this period the holds had to be fully cleaned, dunnage and sparring renewed, and bilges cleaned. This last

job invariably fell to the cadets and the 'chippie' and quickly led to heat exhaustion.

At our stand-bi berth we were moored alongside the Scindia Company vessel 'JALAPUTRA' (1954/5,200 grt),

which soon became known as the 'Jalaputrid', for reasons which I will not discuss here!

Our general comfort and well-being were not enhanced by the presence of the coaling berths on the opposite

side of the dock. Constant clouds of black dust swept across the ship, into every nook and cranny both inside and outside,

as a succession of Bharat steamers loaded their cargoes. This did little for our Chief Officer's gleaming paintwork.

On Monday October 12th, 1959 we commenced loading our homeward cargo, the majority of which was tea (in

chests) for Manchester, London and Port Sudan. At that time, as was inevitable in those days, our subsequent loading

and discharge ports in the U.K. and Continent were changed on a daily basis, making notification of mailing addresses

a complete headache. We also loaded into our strongroom several million pounds worth of opium, under armed guard.

During our stay in Calcutta we struck up a freindship with cadets from the Union S.S. Co., of New Zealand

ship 'WAIRIMU' (1941/3,800 grt).

Completion of loading and sailing was scheduled for midnight on 20th October. However, this was delayed

by a particularly violent storm which hit us at lunch-time that day, during which 'WAIRIMU' and 'BHARATTRA' were torn

from their moorings and driven across the dock into the wall on the opposite side. It took over two hours for tugs to

restore calm and normality.

So it was that our departure was a rather chaotic affair. To quote the Company Agent, 'a typical Clan

Line finish; derricks waving all over the place, gin falls snapping, hatch boards collapsing, winches breaking down, stevedores

sleeping, chief officer tearing his hair, and a furious captain'.

Finally, all the cargo was loaded and we left our berth, only to breakdown immediately with a defective

lubricating valve, causing us to be stuck in the lock for one and a half hours, much to everyone's embarrassment.

To make matters worse, 'CLAN DAVIDSON' (1943/8,067 grt) was waiting in Garden Reach to enter the dock.

She was one of the twin screw 'CLAN CAMERON' class built just before and during WW2, but 'CLAN DAVIDSON' entered service as

the midget submarine depot ship HMS Bonaventure having been purchased by the Admiralty 'on the stocks'. She entered

Clan Line service in 1948 and was scrapped in 1961. At that time she was serving in the dreaded role as cadet training

ship.

Once clear of the river Hooghly we set course southwards towards Ceylon's main port of Colombo. This

was another very congested port with many ships waiting outside for a berth, but as we were calling only for oil and water

we were handled without delay.

Among the many ships in Colombo Harbour were the PO managed trooper 'EMPIRE FOWEY' (1935/19,121 grt), PO

'DONGOLA' (1946/7,400 grt) and the Royal Navy was represented by the 'Battle' class destroyer HMS FINISTERRE.

From Colombo we made the short hop to Tuticorin on the southern tip of India. This was my first experience

of an 'anchor port', many of which were to be found around the Indian coast. There were no harbour facilities, ships

anchored about two and a half miles offshore and cargo was brought out in large sailing dhows, each holding about 75 tons,

and crewed by four men and a small boy whose job it was to crawl along the huge gaff to work the single sail.

The war-built 'Empire' Class ship 'CLAN MACKINLAY' (1945/7,392 grt), ex Empire Fawley, arrived at Tuticorin

shortly after us. Also at anchor were the indian flag vessels, 'INDIAN TRADER' (1944/7,700 grt), 'JALAJYOTI' (1943/6,000

grt), 'JALAPUTRA' (1954/5,200 grt), and 'JAG DEVI' (1943/7,000 grt).

We loaded more tea at Tuticorin, before heading south again to the southern tip of Ceylon and the picturesque

port of Galle. Here we were to load another 600 tons of tea at a leisurely pace, over a period of 10 days. We

were also to load oilcake in bags which had previously been on on fire before being unloaded from 'CLAN MACKENZIE' (1942/7,600

grt).

Galle was a welcome break for the whole crew, with day time cargo work only, there was ample time for relaxation.

Our motor boat was constantly in the water, manned by cadets, for runs ashore and to the many secluded beaches for swimming

parties. I quickly fell in love with this most agreeable place.

Although Galle was the second largest town in Ceylon, it had no quayside facilities for large vessels. Once

ships entered the shelter of the bay four 6 inch hawsers were picked up aft, two on each quarter, and both anchors were dropped

forward. It was not unusual for these moorings to drag in the frequent southerly gales.

Cargo was ferried out to the ship in small oar-propelled lighters each holding about 12 slings of tea chests,

and once our sister ship 'CLAN MACLEOD' (1948/5,997 grt) arrived to discharge cargo, these lighters were in very short supply.

On the 7th November 1959, we sailed from Galle on the first leg of our homeward voyage to London.

Our usual bunkering stop at Aden was unavailable due to a srike, although we did call briefly to load a small amount of cargo,

so we had to bunker instead at Djibouti in French Somaliland. Djibouti was then a very small and usually quiet port

but it suddenly found itself having to cope with all the shipping that normally bunkered in Aden. However, we were in

and out before the queues started to build up.

Our final loading port was Assab, a small Ethiopean desert town which was then just starting to install

modern port facilities. We loaded 400 tons of peas, beans, lentils and particularly smelly camel hides.

The homeward cargo was now complete and 'CLAN MACLEAN' was loaded down to her marks. Number one hold

contained bagged oilcake (ex-'CLAN MACKENZIE'), camel hides, hemp, leather, rubber and coconut oil. Number two had mainly

tea in chests and small parcels of wax, carpets and personal effects. Number three hold had bagged oilcake, tea, mica

and cotton yarns. Number four hold was entirely tea chests and number five had bagged oilcake, camel hides, lentils,

senna and bags of quills. In the locker was cutch, carpets, walnuts and opium. Ports of destination were London,

Rotterdam, Avonmouth, Liverpool, Manchester, Glasgow, Dundee, Bremen, Hamburg, Amsterdam, Port Sudan, Port Said and Antwerp.

The continental ports and Dundee were for transshipment.

Thus, our first unloading port was just a few hundred miles up the East African coast at Port Sudan.

Here we discharged 200 tons of tea and gunny whilst at anchor in mid-harbour, with the help of the famous 'fuzzy-wuzzies'

whose presence was easily detectable due to their special brand of after shave (camel dung!).

Also in port were the Ellerman Hall vessels 'CITY OF LYONS' (1926/7,200 grt), and 'CITY OF PHILADELPHIA'

(1949/7,600 grt), Harrison's 'ARBITRATOR' (1951/8,200 grt) and the Swedish schooner 'ALBATROSS'.

After only 18 hours in port we sailed from Port Sudan and headed northwards towards Suez Bay; a two day

passage. We remained in quarantine during our Suez Canal passage, because of our call at Assab which was a yellow fever

port.

Our north bound convoy of eight dry cargo vessels was led into the Canal by the Anchor Line passenger ship

'CALEDONIA' (1948/11,255 grt), but we were to pause briefly in Port Said to discharge a small quantity of tea chests from

numbers two and four upper 'tween decks. The yellow flag fluttering from our signal halliard served to discourage the

hordes of bum-boat men.

Our departure from Port Said was marked by the lowering and lashing of derricks and generally batterning

down tarpaulins and hatch covers. Bad weather was forecast ahead on the homeward route, but the Mediterranean remained

kind to us, although increasingly cold. We were soon back in the unfamiliar 'blues' and appreciating the hot curries which

were always a feature of our menu.

Among the many ships we passed on the well beaten track between Port Said and Gibraltar was 'CLAN BRODIE'

(1941/7,473 grt), a twin screw turbine vessel, taken over from new by the Admiralty and completed at the seaplane depot ship

HMS Athene. She was not finally delivered to Clan Line until 1946. 'CLAN BRODIE' was typical of the type of vessel

completed for Clan Line just prior to and during the Second World War, of which 'CLAN CAMERON' (1937/7,243 grt) was the lead

ship of twenty. Now almost 20 years old, the 'CLAN BRODIE' was nearing the end of her active life, but she still portrayed

a smart , business-like appearance. Deep laden to her marks, she ploughed eastwards towards Port Said; thick black smoke

pouring from her tall black funnel, the two red bands shining proudly in the evening sunlight.

Other Company's ships in the area included King Line's 'MALCOLM' (1952/5,883 grt) , on passage from the

U.S.A. to Red Sea ports. One of a class of six small motorships built between 1951 and 1958, I was to serve in her sister

'KING CHARLES' 18 months later during a round-the-world tramping voyage.

'ROXBURGH CASTLE' (1945/8,000) was also in the area, one of the Union-Castle 'R' Class fruit boats.

Also seen in this busy part of the Mediterranean were Shaw Savill's 'CRETIC' (1955/11,191 grt), British

India's tanker 'ELORA' (1959/24,300 grt), and Denholm's 'NORSCOT' (1953/12,700 grt).

After passing through the Strait of Gibraltar and heading northwards the weather started to deteriorate

rapidly and a full gale was soon battering 'CLAN MACLEAN', with hurricane force winds ahead of us in the Bay of Biscay.

This was my first taste of really bad weather and I was soon suffering from the mal-de-mer and hoping that I would die!

Ahead of us an ore carrier lost a man overboard and we picked up an SOS from a Liberian ship in ballast

eight miles off the coast with steering failure. We altered course towards her position, which did nothing to ease the

motion of the ship, but the casualty had regained control before we reached her and was heading into Oporto.

Mercifully, as we approached Ushant the winds began to moderate and normality returned to our lives.

Perhaps 'normality' was the wrong word as a strange disease had now afflicted the European members of the crew. When

I enquired I was told that this was a severe attack of the 'channels' and I soon found that I was also affected. Symptoms

included light headedness, sparkling smiles and skipping around the deck shouting, whistling and occasionally kissing each

other!

Off Ushant traffic was heavy and conflicting, in those days before separation zones. We cadets were back

on four hour bridge watches to act as an extra pair of eyes and practise our basic knowledge of navigation under the watchful

eye of the O.O.W. The weather was now calm and fine, 'CLAN MACLEAN' sped up-channel with the flood tide. Off Beachy

Head we were making 18 knots as we headed towards the Dungeness pilot station.

The pilot boarded at 0730 on December 3rd 1959 and we proceeded immediately through the Dover Strait, the

Downs, around North Foreland and into the River Thames, where we docked at East Branch, Tilbury at 1530.

Already in port were P & O's 'STRATHEDEN' (1937/23,700 grt) and 'IBERIA' (1954/29,614 grt). Brocklebank's

'MANDASOR' (1944/7,071 grt), Ellerman's 'CITY OF PHILADELPHIA' (1949/7,600 grt) and 'CITY OF WINNIPEG' (1956/7,700 grt). Palm

Line's 'MATADI PALM' (1948/6,246 grt). Lambert's 'TEMPLE HALL' (1954/8,003 grt) and our own 'CLAN MATHESON' (1958/7,685

grt).

So ended my first voyage and, five days later, I went home on leave over Christmas, with all the airs and

swank of an 'old salt'. My recall orders directed me to join 'CLAN MACLEAN' in King George V dock Glasgow, at 0815 on

New Year's Day.

Obviously, some one's idea of a joke, I thought.

It wasn't, but that's another story."

---------------------------------------------------------OOOOOOOOOO-----------------------------------------------------------------

The following short story has been kindly provided by Derek Lewis and describes

his first trip aboard Furness Withy's "QUEEN OF BERMUDA" as Junior Electrician.

|

|

| Artixst's impression "QUEEN OF BERMUDA" - Courtesy Derek Lewis |

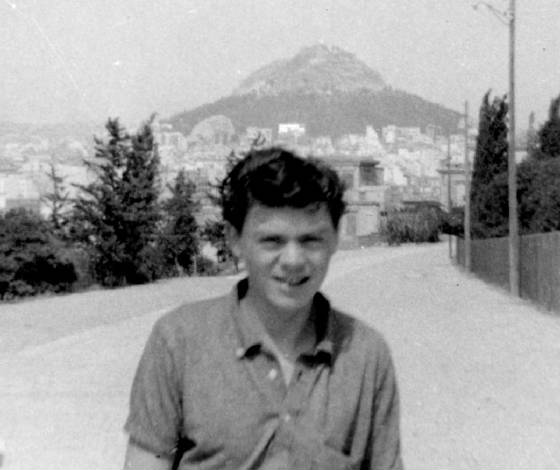

The picture below of himself and shipmates was taken

in 1962 after a refit hence the reception of the fire tugs in the background.

The first lad is Danny Docherty, 4th. engineer in the aux. engine room. Derek as 4th electrician.

Third from the left is Johnny McCoogan, junior engineer and last, Tom Boyce, 2nd

|

|

| Derek plus 'mates' aboard "QUEEN OF BERMUDA" |

It's October 1960 and I'm nearly at the end of my 6 year apprenticeship. (How the young ones would suffer

today if they had to apprentice for 6 years!). In those days we all know what happened when you reached 21 and the end

of your apprenticeship. Ta, ta son, it's down the road for you...............

So, what do we do next? Well, living in Sunderland, once the biggest shipbuilding town in the world,

the thought of going to sea crossed my mind. However, as I had worked in the building industry side of the electrical

services the nearest I had been to ships was watching them launched and berthed in the River Weir.

Never mind, being young and confident I wrote off to the big shipping companies in London and enquired

about going to sea as an electrician. It only took a couple of days for the application forms to arrive.

Well, winches, capstans, generators and swithcboards! What on earth were they? All very strange

to the building services electrician. Being pretty cocky I ticked all the required boxes. "Yes, I was familiar

with all that lot!" and posted off the forms.

A few days later I received a letter from one of the companies offering me a position as a Junior Electrical

Engineer Officer, subject to a medical. Boy, how chuffed I felt. Me, an officer. Naturally I accepted the

offer and off I trotted to the pool in Newcastle for the medical and form filling to get my discharge book etc. We all

know about the medical for the MN. "Read that line", what's that colour? and cough..........

Always wondered if anyone actually failed the medical for the MN!

Next, off to Caslaws, (for those reading this who live or lived in Sunderland, you will remember this as

the naval outfitters) with the list from the shipping company for the measuring and ordering of the uniform plus all the other

items required for sea service.

"And what will you be doing in the MN sir?" "Electrician", I replied proudly. "Ah yes, that

will be a green stripe for you and what company are you joining?" "Furness Withy" I replied. "Oh yes, we have

their house badges here so we can make up your complete uniform.

And so it went on. Scarf, Macintosh, overalls, engine room shoes etc. etc.

At this time in 1960, still an apprentice remember, I was earning 3/9d an hour. I think that was just

over 8 quid a week, 32 pounds old money. So just how was I going to pay for all this fine uniform and accessories.

Back came the response, "No problem, sir. The company will loan you the money and then deduct it from your pay".

Ah, my first taste of the 'never-never'!

|

|

| "QUEEN OF BERMUDA" Built 1933, 22,501 grt - Courtesy derek Lewis |

Then the letter arrived from the London office.

"Dear Mr. Lewis, would you like to join (not, you HAVE to join) the QUEEN OF BERMUDA as a Junior Electrician?

At this time of my life my parents and I lived in a pub which they managed in the docks area of Sunderland

so it wasn't too hard to pick up some information about my very first ship before joining her.

As a cruise liner on the American coast she used to come regularly to the Tyne for her yearly refits.

Just the job!

A nice short taxi ride to Wallsend with my new gear. Or so I thought.

The next letter from London was the travel instructions and railway warrant to join the ship down in Falmouth

which was a day's journey from Sunderland.

11 p.m. SUNDAY, DECEMBER 4TH. 1960.

The beginning of my sea-going career!

There I was standing on the north end platform of Sunderland railway station, mother crying by my side and

me saying.

"Mother, I'm only going to work" but that was the last I was to see of Sunderland for another 11 months.

Long trips were quite often the 'order of the day' back in the fifties and sixties!

In those days trains to London seemed to take forever, especially the night train. Seaham Harbour,

Hartlepool, Stockton, Darlington. You name it, that's where the train stopped!

Eventually we arrived at King's Cross around 6 a.m. and then I hopped over to Paddington to catch the next

train to Falmouth. One good thing about joing a ship travelling at Company's expense one usually could indulge in a

good meal.

So, arriving at Falmouth late in the afternoon I took off down to the waterfront and saw this rather huge

(by 1960 standards anyway!) grey and white liner complete with three funnels. I had never seen anything like this on

the Weir. The crew seemed to be leaving with all their gear so I was going in the opposite direction it seemed.

Were they rats deserting a sinking ship - was there something I hadn't been told about this particular ship!?

Stores all over the deck, shipyard workies with their tools etc. Complete chaos, or so it seemed to

this 'rookie'.

At the top of the gangway I was instructed to go to the purser's office to report and be assigned to a cabin.

Boy, what a pleasant surprise. A very nice 'spot' on "B" deck, my own toilet and shower. Pretty well everything one

could ask for. What I didn't know at the time was that this was only a very temporary assignment as the 'ginger beers'

and 'leckies' were installed down on "E" deck. Not quite as fancy I discovered later but quite satisfactory nonetheless!

Tuesday morning and breakfast in the main dining saloon along with the rest of the engineers and our other

departmental 'shipmates'. Deck officers and 'sparks'.

Again, this was to be temporary as segregation was the order of the day for the engineering staff aboard

the "Empress".

Once the ship was 'running' normally with a complement of passengers we would again be moved down to "E"

deck.

For the next 6 weeks it was a case of finding one's own way around the ship, check the shipyard lads work

and generally settle in for the voyage.

One thing I shall always remember about that first week.

I joined her on the Monday so by the middle of that week I did have some idea as to the 'correct' dress

at mealtimes i.e. full uniform.

One of my electrician mates from back home, unknown to me at the time, had also joined the "QUEEN OF BERMUDA".

He had joined late on Wednesday night.

At breakfast Thursday morning in he strolled to the dining saloon, straight out of his bunk, slippers and

rolled up shirtsleeves, just like at home. BIG mistake!

Following breakfast the Chief 'Leckie" asked me to inform my 'friend' that he was not to arrive in the dining

saloon looking like a cowboy and to be 'correctly attired' in the future...........

|

|

| Derek in his pristine 'Nr 10s' |

Middle of January 1961 and we sail from Falmouth on our way to our base port of New York, 5 days of pure

hell!

I did eventually cross the North Atlantic a number of times but this first trip was the worst. No

stabilisers in those days, just good ol' 'rock & roll' with repeated trips to the deck rail or the nearest head.

By this time I'm installed in my cabin down on 'E' deck.

At the time of sailing we were instructed to close port holes and dead lights. Soon some of the lads

who either didn't hear the order or chose to ignore it found out why they had to be closed. For the sleeping watchkeepers

it could get very wet.

We arrived at Pier 95, West 55th Street on a Wednesday morning in the middle of January and New York was

FREEZING! On docking days the electricians usually worked until noon then, if not on standbi that day, we'd have the

rest of the day off. So, a quick lunch and then off to see the "Big Apple". Broadway, Times Square, all

the sights and big attractions for first trippers. Following sightseeing it was back to the ship for dinner and a few

cans, quite a few in fact, and then off again for a visit to the Merchant Navy Club. One of the electricians, Joe Steel,

missed that first night. He collapsed at the top of the gangway. We always said it was the cold that hit him coming

out of the warm accommodation. Nothing to do with the amount of ale he had consumed, of course.............

|

|

| Derek, young but no longer innocent..... |

Saturday dawned and the passengers arrived for the years first cruise to Bermuda. Being January most

of the passengers at that time were the 'blue rinse' brigade, not one under 60..............

However, we first trippers were informed by the seasoned crew members that, come Easter, things improved

considerably when those lovely student 'maidens' come for their spring cruise.

By this time I had been assigned the 4 to 8 watch in the engine rooms. Saturdays and sailing days

you would work the morning from 9 to 12 on duties as required then dash up town for some quick shopping and back for standbi

at 2 p.m.

By that time the passengers would be boarding and the band would be playing on the dockside. All very

festive indeed.

At 3 p.m. on the dot the engine room telegraph would sound and 'slow astern' would be the order from the

bridge. Off down the Hudson and a short 36 hour trip to the island of Bermuda.

By this time the routine of the day to day life was well established. As I mentioned, segregation

was still the order of the day as regards who could go where on the ship. The engineers were only allowed on deck between

9 a.m. and 6 p.m. and, with the exception of going to the movies, could not mix with passengers.

We had our own dining room and smoke room etc. The day time electricians, working among the passengers and

on the decks, had the enviable job of 'checking out the talent' for the parties. Mix with the passengers? Well

not officially, but you could bet there would be a party in the engineers lounge most nights. It was certainly a game

dodging the Masters-at-Arms and getting the guests down to 'E' deck to show them the 'golden rivet' etc.

Monday 8-9 a.m. and docking at Hamilton, Bermuda. One big difference from New York! Nice and

warm although I would later be saying otherwise in the summer months sweating down in the engineroom. On docking days

you would do your watchkeeping hours and then, following breakfast, work from 9 to 12 with the rest of the day off.

First day in Bermuda and first day in a warm climate it was off to Elbow Beach and pink coral sand.

One helluva difference from Roker & Seaburn Beach back home I can tell you.................

Again the first trippers learned their lesson about warm climates. A couple of the 4 to 8 watch keepers,

being up most of the night partying, fell into an alcohol induced sleep on the beach and got royally burned for their trouble.

In the summer months we often got a laugh parading around the decks in our tropic 'whites' and would often

get requests from passengers to serve them drinks. I suppose it was understandable as it was somewhat easy

for us to be mistaken as catering staff or waiters. You can imagine some of the replies they received from the more

'earthy' Glaswegian engineers!

Our stay in Bermuda would last until around 3 p.m. on the Wednesday and then we were back to New York for

8 to 9 a.m. on Friday which was, more or less, the routine for the next 9 months. It did, however,

change occasionally when we were to make a couple of trips down to Nassau which meant arriving and leaving New York on the

Saturday. Once, when we hit the back end of a hurricane and didn't get back to Bermuda until the Wednesday, quite a

few of the passengers left and flew back to New York.

After 9 months we came back to Belfast for a 6 month refit which included new boilers and new accommodation.

This included moving the engineers up a couple of decks which meant a longer run when the engine room alarm went off!

Another big change was the removal of two of her funnels.

I did a second trip before going into cargo passenger liners, tankers and ore carriers.

What a change in both working conditions and attitude amongst the crew members, especially the 'mates',

as they had now become known by!

|

|

| "QUEEN OF BERMUDA" following her 1962 refit - Courtesy Derek Lewis |

Some good points I remember about my first trip...............

As far as my home town was concerned some changes did occur in my absence. When I left Sunderland

for the first time we still had bomb sites and barrow boys in town.

Going on the 'Queen' and finding out that you ate the same food as the passengers i.e. 6 course breakfasts,

lunches and dinners with 'smokoes' in between was simply not expected.

Being actually woken up for 'work' with a cup of tea (which normally went cold and had to be poured down

the sink!)

People calling you 'Mr. Lewis'. There was even a time when this was brought to a point...

One day, while doing daywork on the passenger decks, the Purser's Office made an announcement over the PA

system for 'Lewis, Electrician to contact the Chief Electrician' - before I could find a 'phone there was a second announcement.

'Would Mr Lewis, 4th Electrician please contact the Chief Electrician?

Well, when I think back now it was really all 'bull' but made this young fella feel pretty important.............

Being so impressionable at that 'young age' some of one's shipmates are indelibly printed in our minds,

seemingly for ever. The Chief Electrician, Al Watson. 'Put one in there son' was his favourite saying meaning

- 'Put a light bulb in that light fitting'.

The Chief Engineer never spoke to a lowly 4th Electrician, of course. When the engine room alarm went

off he would be there most times in his best white uniform which soon became covered in oil etc.. He, of course, didn't

have to buy his!

The rest of the engineers were mostly Scots (now why is that!?).

On a sad note, for whatever personal reasons (the fabled 'Dear Johns, perhaps!?) a couple of engineers,

with whom I was on watch with on later ships, jumped over the 'wall'.

I suppose being away from home for an extended period affected different people in different ways.

Dislikes about the first trip?

The Engineroom loudhailer 'phones. One would listen to the 'message' with difficulty due to general

distortion and 'noise' coming at you from all sides.

Getting up at 4 a.m. for watch.

Having to get the 8 to 12 watch keeper 'leckie' up so you could be relieved, especially following one of

his 'benders'!

Probably a few more that escape me right now but one could always go around singing the Beach Boys "I Want

to go Home' which seemed to help.

Now, what was always great was getting back home to the office in Newcastle and picking up a few hundred

quid in back pay and meeting some of your old mates and bragging about it all................................

|

|

| Derek today, no longer at sea but with happy memories............................. |

So ends Derek's 'baptism' to his 'career at sea'.

We hope you have enjoyed these memories and if any reader has a similar story

to tell or would like to contact Derek please communicate via the site manager.

ooooooooooOOOOOOOOOOoooooooooo

STUART JONES - SENIOR CADET CUNARD S/S CO.

|

|

| Cunard's "ASSYRIA" - Courtesy Stuart Jones. |

In November 1956 I was the senior apprentice on the Cunard cargo vessel

Asia.

Cunard had two other cargo vessels ships identical to Asia these were Arabia &

Assyria.

Two hatches forward of the bridge, one hatch on the boat deck and three hatches aft.

We had part loaded in Montreal and finished loading in Quebec. The Master was Captain F.E Patchett known in the company as’ Foggy Patchett’

He had served his time in sail and this was his last trip before retiring.

We left Quebec in the afternoon and were in the channel under the pilotage of a Mr

Cloutier passing Orleans Island

during the Mates watch.

The other apprentice, Willie Stevens and I were off watch below in our cabin when there was an almighty bang. We dashed out on deck and found out that we had

collided with an inbound cargo vessel – the Wolfgang Russ.

After all of the melee had died down we were towed back to Quebec and berthed at Wolf Cove. We later found out that the Wolfgang

Russ had had to be run ashore as she was in danger of sinking.

Once alongside we found that our bow from a couple of metres above the waterline to the forefoot was bent round like

melted toffee.

The No.1 hold in the Asia was a deep tank and had been loaded with ‘Bush Peas’ in bulk The bulk peas were

secured with bagged peas to prevent shifting.

General cargo had been loaded on the tank top

No.2 lower hold was part filled with grain with logs and general cargo in the tween decks.

It was found that the force of the collision as well as having bent the bow round had also fractured the collision

bulkhead with the result that No 1 hold which was full of the dried peas was flooding.

Although the massive hinged tank top lid had not been secured the securing dogs had all been engaged.

Soon it became apparent that the peas were expanding at a rapid rate as the whole of the tank top was gradually rising.

Due to the expansion in No.1 hold taking place in all directions the bulkhead between No.1 & No.2 holds was also

starting to fail. Water was streaming out from numerous places and falling onto the grain in No.2.

As inevitably the ship would have to go into dry dock it was necessary to try and discharge as much cargo as possible

beforehand. This discharge was getting more and more frenetic as if the bulkhead

was to seriously fail with Nos. 1 & 2 flooded it was possible that the ship would sink alongside.

While the discharge went on people from Davy’s dockyard at Lauzon, on the opposite bank of the St Lawrence were

in No.2 hold trying to weld cofferdams over the worst of the leaks from the bulkhead.

After about two days it was decided to put the ship into Davy’s dry-dock. The collision had taken place on the

last day of November and it would have been our last trip before the river closed

for navigation for the winter.

It was a Sunday afternoon and there was a blizzard blowing when we left

the berth and were towed to Lauzon stern first to avoid forward pressure on the bow and bulkhead.

Eventually we got there and the ship was settled on the blocks.

It was still necessary to empty the No.1 hold for repairs to commence.

It was decided that the most practical way to empty the hold was to cut four holes in the shell plating – two

on each side of the No.1 hold bilge and let the wet peas run into the dry-dock.

At first the wet peas ran out in a stream however after the first cascade had stopped it was found necessary to have

people inside the hold shovelling the peas towards the holes and also necessary to have people in the bottom of the drydock

shovelling the peas away from the hole.

I don’t know whose idea it was – probably Cunard’s idea to use the crew to do this. Anyway it was

like winning the pools for us apprentices as we were paid something like three Canadian dollars an hour. At that time apprentices

were paid £10 per year in the first year, £15 in the second year, £20 in the third year and £25 in the last year plus

£25 on satisfactory completion of indentures !

I think we worked something like twenty hours and earned riches beyond

our wildest dreams !

We were paid out promptly in cash. That evening, after we were paid Willie Stevens & I then got our go ashore gear

on and went across to Quebec. It was necessary to cross

on the ferry from Levis to Quebec

and I well remember the ferry having difficulty getting alongside due to the ice which already was starting to form on the

river.

As soon as we hit Quebec we made for a night club

called Bel Tabarin and started spending money like the proverbial drunken sailors.

We met up with a couple of girls who were sisters and off we went to their apartment for a good time.

By the time we surfaced and got back to the ship the following morning we were both totally broke !

Life was pretty boring with little to do in the evenings other than surreptitious

drinking as drinking was definitely not allowed for apprentices.

Soon the ship ran out of beer.

Willie and I were then picked to go ashore and get some beer so a sledge

was made and off we went to the liquor store to get in some supplies.

As we were getting the beer back on board we were spotted by the mate and given a severe bollocking, threatened with

cancellation of indentures etc, etc.

Soon after we were put in the dry dock the Wolfgang Russ was put in the other half of the dry dock. I cannot recall

any fraternising between the crews but I remember having to go with some of our crew to recover some of our forecastle stores

which finished up in the officers ward room on the German ship.

The Wolfgang Russ had been split from the bulwark to the bilge and our bow had almost penetrated to the mid-ship line.

Davy’s yard was large and in the winter ‘Lakers’ were laid up there in dry-dock. One night Willie

and I had been ashore in Lauzon in a bar and had fallen out of there in the company of a couple of the crew of a Laker called

the Saskatoon. They invited us back to their ship and took

pity on us thinking we were all starving back on the Asia. They then commenced to knock off

the lock on the galley store and gave us a small side of bacon.

We staggered back to the Asia and no doubt scored a few brownie points with our Chief

Steward.

The repair in Quebec was only to be a temporary one to enable us to get round to Halifax, Nova Scotia for a permanent

repair to be made.

The St Lawrence was getting more and more ice bound as December progressed and finally just before Christmas we left

Lauzon, preceded by the Canadian ice breaker

McClean. At this time the ice was only three or four inches thick and was not really a problem. Nevertheless the ice

breaker went with us as far as Father Point.

By this time poor old Foggy Patchett had been relieved. It must have been a great tragedy for him after serving his

whole working life at sea and finally coming to grief on his last trip.

On arrival at Halifax we went straight into the Navy

Dockyard and the permanent repair commenced.

At that time the Canadian Navy’s frigates were doing anti-submarine

training with British submarines which were temporarily based in Halifax.

This training took place southwards from Halifax as far as the West Indies.

There was a British submarine tied up in the dockyard not far from where we were in dry dock. Normally the Merchant

Navy and the Royal Navy have a healthy disregard for each other however for some

reason the officers from the submarine and our Mates and Engineers struck up some sort of understanding which resulted in

copious amounts of liquor being consumed. One night they would come to our ship and then the following night we would all

go to the submariners. As apprentices we chummed up with our opposite numbers - the midshipmen. It was a great experience

getting shown around submarine .

The main attraction in the town was the YWCA where regular dances were held. I remember in the depths of winter walking

along the main drag in Halifax on our way to the ‘YWCA’

with the snow piled so high on the pavement that you could hardly see over the top of it.

Both Willie and I got fixed up with girlfriends. Mine shared a flat with two or three other girls. As far as I can

remember it was like being in a dormitory. I cannot remember the name of my girlfriend

but I well remember Willie’s girlfriend’s name was Louise as I called him up on New Years Eve from my girlfriends

flat singing ‘Every little breeze seems to whisper Louise’

We spent about three months in Halifax before the repair

was completed.

----------ooooooooooOOOOOOOOOOoooooooooo----------

Stuart Jones has kindly provided an account of his first trip to sea back in

1952 when going to sea was not the comfortable experience it evolved into in later years...............a short 'bio' of his

career is also provided below.

|

|

| "ELIDIR' - Courtesy Stuart Jones |

.

"I completed my indentures with Cunard in 1957 and got Second Mates & Mates tickets in 1960. However

between mates and Masters I got pneumonia and was paid off sick in Genoa in May 1961. The pneumonia developed into milliary

TB and eventually I got TB spine. I was repatriated to the UK and spent until the August following year recovering.

I decided

that as I was by this time engaged and doubtful whether I could go back to sea to seek work ashore.

I started with

the Liverpool & Glasgow Salvage Association,a ship salvage organisation, in a clerical capacity on the bottom rung of

the ladder. This was with a view to a career combining my limited seagoing experience and studying marine insurance.

However

the pay was abysmal and so I left and joined a firm of Produce Brokers as a broker. This was difficult work as brokers were

generally paid by the seller the sum of 1% of the selling price.

An offer of a job working for a metal assaying company

as a representative came up so I jumped ship again. The work involved protecting the interests of sellers who were selling

metal scrap, minerals and ores to refineries and smelters.

This eventually resulted in me travelling almost literally all

over the world.

By a strange quirk of fate although on the face of it the work had no relation to seagoing, the company

became involved in the weight determination of bulk cargoes of minerals by difference of vessel's displacement ie Draft Survey.

Suddenly I was the only one in company with the ability to undertake such work.

I spent the next thirty six years doing

this job during which time I also lived in Hong Kong for five years and worked extensively in China and the Far East.

I

retired in 2001 and continue to do part time work in the UK for the company.

As a result of working in Hong Kong

I bought a 29 ft sailing boat in 1991 and have sailed it, mainly singlehanded in the English Channel to the Scilly Isles,

Channel Islands and North Brittany."

First Trip

In 1952, the year before officially I went to sea, I did a couple of trips on a coaster called the 'ELIDIR'.

My father worked for a grain and flour importer in Liverpool who chartered ocean going and coasting vessels as part of their normal trading.

During the school summer holidays he was able to arrange a trip on the 'ELIDIR' from Birkenhead to Glasgow.

The coaster was loading at Ranks Blue Cross Mills in the West Float with a cargo of flour in bags and I joined her

there.

I was fifteen and a half at the time. My father took me from where we lived in West Derby, Liverpool

down to where the she was berthed.

The 'ELIDIR' had been built in 1905 by the Ailsa Craig Shipbuilding Company at their yard in Ayr.

She was propelled by a coal fired triple expansion steam reciprocating engine.

There was no generator so no electricity. Steering was manual rod and chain, assisted when manoevering by a steam steering engine.

My bunk was to be on the settee in what passed for the chartroom and the Old Man’s day room below the bridge.

As far as I can remember there were about eight crew – the skipper, the mate, an engineer, a greaser a couple

of firemen and a couple of sailors and a cook

It was a Saturday afternoon when we arrived on the quay and we could see

no sign of anybody. After some hollering and shouting eventually a seamen emerged from the forecastle and helped me with my

gear.

His name was Tim and he came from Clear Island

on the south west coast of Ireland. After

sorting out my bunk he offered me a cup of tea in the fo’csle.

The crew lived forward. The greaser and the two firemen on the port side of the fo’csle and the seamen on the

starboard side.

There was a coke fired, pot bellied stove in the middle on which was a pot of tea simmering away. He poured out two

mugs of tea and then took a tin of condensed milk -‘conny onny’ and proceeded to blow in one of the holes in the

top of the tin to force out the ‘conny onny’ into the mugs. I was really impressed and felt I was now among men

!

Eventually the crew returned and then the skipper accompanied by his wife and off we sailed down the Mersey.

I can’t really remember how I passed the time away during the trip although I do remember the skipper giving

me my first lesson in chart reading by the light of an oil lamp. Of course I had a go at steering. The wheel must have

been at least four feet in diameter in order to get a purchase on the drum around which the steering chain was rove.

Going into or out of port the steering engine was clutched in to help the helmsman. I distinctly remember the intermittent

'bang, bang, bang' as the wheel was turned and the steering engine jumped into

life.

We progressed up the Irish Sea and called up Port Patrick radio as we passed through the North

Channel. It was probably on Medium wave as there was no VHF then.

Passing Ailsa Craig and the Cumbraes we eventually picked up the pilot

off Greenock and sailed up past John Brown’s yard to tie up in Glasgow Docks.

In 1952 Glasgow was still in more or less full tilt

building ships and an important general cargo port.

I think we were in Glasgow for a couple of days. The

berth we were in was near to the Gorbals and Kelvin Haugh and at that time was pretty rough. Despite my fifteen and a half

years I went ashore with the seamen but I guess it was for no more than fish and

chips or such like.

As we walked back to the ship I vividly remember seeing some unfortunate drunk in a shop doorway drinking from a broken bottle with blood running down his chin. A common sight in that city !

While we were in Glasgow

the mate decided that it was time to renew the shackles which attached the steering chains to the steering quadrant.

The quadrant was under a grating on the poop. The grating had been removed and one of the crew was having to hacksaw

the shackles apart as the pins were so corroded.

Being young and over enthusiastic I asked if I could have a go at sawing. Of course I went at it like a bull at a gate

and the hack saw jumped out of the cut and across the thumb of my hand which

was holding the shackle. Although it was a deep cut and through the nail it did not go as far as the bone.

I got up and sucked the blood off my thumb and, playing the tough guy, said I was OK and wanted to restart the sawing.

Tim, the Irish man, said I should go along to the galley and get a hot drink. After a little mild protesting I went

along to the galley and the cook sat me down with a steaming hot cup of sweet tea. The next thing I knew I was sliding

off the bench onto the deck as I passed out.

It was a classic case of shock.

Eventually we completed discharge and left again for Birkenhead. I helped to sweep

out the hold and prepare it for another cargo of bagged flour.

The next job I tried was helping the fireman in the stokehold. The bunker was on the forward side of the stokehold

and there was a space for the fireman to work and on the after side were the fires. I recall that there were three grates

heating a fire tube boiler.

The coal was fed by gravity from the bunker which extended right across the ship onto the tank tops through small hatches from where it was shovelled or pitched into the fires.

The fireman, I remember, suffered from some sort of disability which forced him to walk unevenly and with a kind

of lurch. Whatever the disability was he made up for it in the strength of his arms which were like legs of ham!

Periodically the fires had to be raked with a ‘slice’. This was a steel shaft with a short piece

of steel at right angles to the end of it.

Beneath the grate was a bar at the front of the firebox. The slice was placed over this and the pointed end projected

between the fire bars. The slice was then worked fore and aft to break up the clinker and allow the ash to fall onto the bottom

of the fire box.

The ash was then raked out of the firebox onto the tank tops, wetted and allowed to cool.

It was a joint effort with the seamen to hoist the wet ash out of the stokehold and dump it overside.

There was a single whip shackled to the fiddley deckhead. A seaman would stand on the top grating in the fiddley while

below the firemen would fill large cans with the ash. The can was then hooked onto the single whip. The fireman then

hoisted the can up to the seaman who unhooked it, took it to the ship’s side and dumped the ash.

He brought the can back hooked it on and lowered it down.

Anyway that was the theory !

I remember working in the stokehold filling the cans and hooking on when I heard this almighty shout from above.

Looking up I saw a can whistling down directly at me. The seaman had not hooked it on properly and had just kicked

the empty can off the grating into space.

I did manage to step sharply to one side and the can loaded with the sodden

remains of ash landed with a bang on the stokehold tank top . Times have changed with the HSE !

I don’t recall anymore dramas but in any event it did not put me off going to sea as in the following year I

signed indentures with The Cunard White Star, as it was known then !

ooooooooooOOOOOOOOOOOOOOOOOOOOoooooooooo

Sailing Close to the Wind

by Ray Simes

These are the random recollections of an old man, the events that I describe all happened a life-time ago, back in

the 60's. And they happened at sea. This is no biography, that would take a volume,

these are just snippets to accompany my photographs. The photographs are mostly of ships and scenes. I wouldn't like to “name

names” or show photographs of any person without their knowledge and consent.

I wear no rose-coloured spectacles when I look back at those years, I bear no recriminations against the sinners, and

I cherish the memory of the saints and the wonderful souls that I also sailed with. Life was like the ocean waves, with high

crests and low troughs and I cannot appreciate the highs without acknowledging the lows. However, I have deleted three sections

in case anybody reading this may be upset by them. (The un-edited version on request from my email address at the end).

I was always going to go to sea. I was born in Liverpool, on the banks of the great River Mersey, before parts of it became

a pond for small pleasure craft and the rest a berth for tankers and container ships. As a small boy I stared with wonder

from the landing stage at the great vessels that paraded there. After my mother died I was deposited into a charitable orphanage.

I escaped regularly to the river. I could walk the seven miles of docks from the Herculaneum

in the south end to the Gladstone in the north. I knew all

the docks' names and all the ships berths. I knew the ships' names and their colours and their owners and their trade routes.

Trespassing the Liverpool docks was difficult, because each entrance on the dock road was

guarded by the police, the best way was to use the landing stage to enter the docks from the sea wall. Birkenhead was much

better, the docks were open and criss-crossed by the seven bridges. The only policeman was on trafiic duty at Duke Street. It was easy to evade the negligent gangway men and

I would walk the alleyways of Clan boats and see the lascars asleep four to a cabin which they shared with their bicycles.

I breathed in the heady heavy oil fumes from the engine-rooms and savoured the smells of exotic spices and foreign cargoes.

I was 15, in my last year at the school and it was the annual sports day. We were all kitted out in our PE gear –

rough shirt, baggy shorts, and running shoes, nothing else. I was delegated to escort a prominent member of the board of governors.

I was naive but not stupid and it was quickly apparent that he was more interested in me than he was in the sports field.

He asked me what I wanted to do when I left school at the end of the term.

“Go to sea” was my reply.

This prominent member of the board of governors was acquainted with other directors of commerce in the city and as

a result he took me to Riversdale Technical college in south Liverpool and introduced me

to an Alfred Holt director. He was a dapper, bespectacled character with a staccato voice and an intermittent stutter. It

was like being barked at by a dog, or quacked at by a duck.

I had thought that I might apply to Marconi in Rumford Street (I had no aptitude for the engine room and my eye-sight

precluded me from deck duty) but as a result of my interview I found myself instead being kitted out at Greenbergs in the

uniform of an Elder Dempster purser cadet.

I was lodging in Speke, a stone's throw from the airport, when I was told to report to the steps of India Building in Water Street with my kit, at 7am one fine summer's morning. I was told nothing else.

I managed to get a lift and left Speke at 6am, travelled out through Garston, Aigburth, and into town. I joined a group of

total strangers (officers and crew) in Water Street

and we all boarded a coach. The coach turned around, headed out of town, through Aigburth, Garston and back to Speke (airport)!

I could have walked there. Apart from Pwhelli (Butlins) in North Wales, and a trip on the

steamer “St Tudno” to the Great Orme (Llandudno) I had never been anywhere. When the charter DC3 Dakota of Dan-Air

took off, I was trembling as much as the plane's old wings were.

Rotterdam, where we seemed to fill the whole ship with Heineken. Antwerp,

Dunkirk, Rouen. I should have

lost what innocence I had to a harlot in Hamburg, but lost

it instead to the Chief Steward in his cabin a few days later.... I had just

turned 16.

In my own company I was bold, resourceful and artful, but in the company of others I was painfully shy, nervous and

literally out of my depth. I kept getting lost onboard and missed meals rather than admit that I couldn't find the dining

room. I was vulnerable and an easy target, but that all soon changed.

The actual transition from school to sea was a natural one for me; I just swapped one uniform for another, one set

of rules for another set, I certainly wasn't used to going home every night and so I didn't have to suffer the trauma of homesickness.

(It upset me to hear first-trippers crying themselves to sleep with homesickness). Seasickness

was something else that luckily did not effect me.

It was the silence that woke me up. After the constant throbbing of the

Doxford engines, day and night, the ship was quiet and rolling on a swell. Dazzling sunlight was pouring through the porthole.

I quickly dressed and ran out on deck. The horizon was empty and shimmering. I ran to the port-side and there was the mountain of Freetown, Sierra Leone. My heart was bursting with excitement. I never lost that sense of

wonderment or privilege.

At the end of the voyage we berthed back in Rotterdam.

Nobody explained to me about “signing off”, so as it was a crisp Autumn morning, I took myself off for a walk

around the neighbourhood. I returned around lunchtime to find the ship deserted with only a Dutch gangwayman for company.

I was not very popular by the time I got signed off and caught up with everyone else waiting at the airport.

The only way to approach New York is from the sea.

I was 17 and on the “Sherbro”. It was dusk and on the horizon the skyscrapers stuck up like distant telegraph

poles. I recognised immediately the silhouette of the liner “France”

as it sailed outward. We sailed under the Verrazano Bridge which was still missing its final central section. We berthed in Brooklyn.

The Beatles were causing hysteria in the country and in a club in Greenwich Village I watched

a young man named 'Bob Dylan' perform.

On our last day in New York myself and two other

cadets were walking back to the ship. A big yank-tank drew alongside and a slick salesman claimed he was a rep for “Crown

Colony” and could let us have a couple of their famous shirts cheap. I had no dollars left but the other two handed

over their money and the car accelerated away in a cloud of dust. Back onboard the opened boxes revealed their contents to

be 'collars and cuffs' only, dummies for display.

I always loved thunderstorms, but I loved storms at sea better. On the mailship APAPA in 1963 we hit a storm in the