|

The following memoirs are those of an ex Radio Officer of the U.S. Merchant Marine.

BOB LION spent his last years in Port Vendres, a small fishing port on the Mediterranean between the Spanish border and the

city of Perpignan, at the foot of the Pyrenee Mountains.

PART ONE

Bob Lion retired from the U.S. Merchant Marine in March of 1991. His sea-going career commenced

at Christmas Eve 1954 and continued for 10 years aboard Liberian flagged tankers, bulk carriers and dredgers.

Following another short 'career' as radio mechanic for Pan American Airlines he then returned to

his beloved 'high'seas' as Radio Officer from february 1979 until his present retirement. He is now living in France.

While many of us stayed at sea for a relatively short period Bob made it his life and diligently recorded some of the more

interesting aspects of his career. It is my pleasure to include an abridged version of his 'story' on the site.

On board MV MARINE PRINCESS (WNLH) of Marine Transport Lines

Summer of 1988

----------------------------------------------------

FORWARD

11th

July 1999 : The last day of CW transmissions from KFS and KPH coast stations. It is the end of an era. This motivated me to

write my own recollections to bear witness to a lesser known period of the history

of the maritime industry. (*)

Today, the ship-going

Radio Officers have joined the dinosaurs and become another “disappeared species”.. However, no Green Peace or

other ecological organization is trying to preserve them. The “Sparks” will be part of the “Romantic Past”,

of the “Legend of the Sea”, joining the square rigged clipper ships. In Europe and elsewhere, coast stations are

closed. The US Coast Guard does not stand a CW watch on 500 kHz. Only the faithful nostalgic “ham” radio amateurs

still use Morse code today. On merchant vessels, a licensed engineer is maintaining all the electronic gear; the captain or

chief mate communicate with the shore via satellite and H.F radiotelephone and a

complex automatic distress signaling device (the “GMDSS”) , instead

of the traditional ‘SOS’ in Morse code, will transmit distress calls.

Maritime literature abounds in books of facts and fiction, about the

sailing ships, the men of war, the heroic deeds of many a brave sailor. Once in a while a story tells of the gallantry of

the Titanic Radio Officers on that fateful night when they called for help, in the pioneering days of maritime radio communications.

I have rarely in these books found any descriptions of the life and work of the Radio Officer. – But in the year 2000,

the San Francisco Maritime Museum dedicated two floors of its beautiful building between Fort Mason and Fishermen’s

Wharf to the history of Maritime Radio Communications. And last year I discovered on the Internet Ian Coombe’s absolutely extraordinary website “Merchant Marine Nostalgia”.

It could be that in a few more years the only vessel of the US Merchant

Marine flying the American flag may be the brave old Liberty Ship SS Jeremiah

O’Brien, which made the return journey to Normandy in June of 1994. You can visit her at the Fishermen’s Wharf

in San Francisco. In 1984, the last American-flagged passenger vessels departed

from Pier 32 for their cruise around Latin America. They were the four sister ships

Santa Mariana, Santa Mercedes,

Santa Magdalena, Santa Maria, of the Delta (ex-Prudential, ex-Grace) Lines. I sailed on all four of them.

Contrary to the famous Greek “tycoons” like Onassis, Niarchos, Livanos and the others, not much was known about the American shipping magnate D.

K. Ludwig and his vessels built at the former Japanese Imperial shipyard of Kure, on the Inland Sea, until I discovered Mr. A. Davis Whittaker’ website

(his

father had sailed as Engineering Officer for National Bulk Carrier) . I took

the liberty of inserting extracts (lists

of ships and , photos) in my “memoirs”

Then I read the

following publication:

“The Invisible Billionaire: Daniel Ludwig”, by Jerry

Shields. Published by Houghton Mifflin Company, Boston, MA, 1986. “

I sailed as Radio Officer aboard

many of the ships of National Bulk Carriers / Universe Tankships .

I have researched into my souvenirs to bring back my life “as a seaman”. Unfortunately,

time has a habit of erasing some information such as names of people, exact dates, description of places, facts and events

in their chronological sequence. But all that I write about happened, existed,

and is true. I did my best.

* written

in 2000, revised March 2006

I dedicate this narrative

of my memories to

To all the ”Sparks” of the World’s Merchant Marine

To all my old shipmates…

SUMMARY OF SEA SERVICES

Liberian Flag

SHIP / Call Sign Type of Vessel

Company Voyage details Dates: from to

___________________________________________________________________________

SS PELOPS/ELCG Greek

Freighter - Scrap Iron

Dec 1954 - Feb 1955

BOSTON - ROTTERDAM

- AMSTERDAM - NEW YORK

_________________________________________________________________

PETROQUEEN/ELHU Universe Tankships

(D.K. Ludwig)

Apr 1955 - Jul 1956

Tanker

SAN FRANCISCO - SAN PEDRO - KAWASAKI/YOKOHAMA - SUNGAI PAKNING (Sumatra)

–

UNIVERSE LEADRER/5LCN Universe Tankships

Sept 1956 - July 1957

(D.K.

Ludwig)

At the time the largest (85000 DWT) tanker

in the world built at KURE / Japan

- NBC shipyards

KURE - SUNGAI PAKNING (Sumatra) - SAN

FRANCISCO - MENA AL AHMADI (Kuwait) – SANTOS (Brasil) - CAPETOWN( for drydock) - SUNGAI PAKNING - SAN FRANCISCO (RICHMOND)

____________________________________________________________________________

ORE REGENT Ore carrier National Bulk Carriers

August 1957

(DK Ludwig)

MORRISTOWN/PA - PUERTO ORDAZ(ORINOCCO RIVER Venezuela)

- MORRISTOWN/PA

____________________________________________________________________________

UNIVERSE CHALLENGER /5LPX Universe Tankships

Sept1957 -

Mar 1958

later re-named FRISIA same as 5LCN - KURE –

SUNGAI PAKNING - SAN

FRANCISCO - KURE (for dry-dock) - SUNGAIPAKNING - LONG BEACH

(HUNTINGTON BEACH) CA

____________________________________________________________________________ST ANNA O/5LBD Maritime

Overseas Corp T2 Tanker Apr 1958 – Jan 1959

(“tramping”)YOKOHAMA - QUATAR - MITSUHAMA/Japan - PANAMA CANAL - BALTIMORE

- PUNTA CARDON/Venez. - BOSTON

- AMUAYBAY/Venez. - ARUBA - NEW YORK - SANTOS/Brasil

- CARTHAGENA/Colombia - CALLAO/Peru – PORTLAND /Maine

____________________________________________________________________________

SS ORE MERIDIAN/5LZI National Bulk Carriers

May - July 1959

- Ore Carrier

(DK

Ludwig, built at Kure) KURE

- PANAMA Canal - PUERTO ORDAZ(Orinocco-River, Venezuela ) - BALTIMORE

____________________________________________________________________________SS ORE CHIEF/ELKM National

Bulk Carrier - July

- Aug 1959

- Ore Carrier

NEWPORT NEWS

- PUERTO ORDAZ(Orinocco-River, Venezuela)

-MOBILE/Alabama

____________________________________________________________________________SEAWAY

National Bulk Carriers - dredge

Sept 1959

dredging BLACK WARRIOOR LAGOON,

BAJA CALIFORNIA/ Mexico

SAN

PEDRO, CA FOR DRYDOCK

SHIP / Call Sign Type of Vessel

Company Voyage details Dates: from to

___________________________________________________________________________

DREDGE ZULIA/5MBC Nional Bulk Carr

Oct

1959 – July 1960

(DK Ludwig)

Dredge chartered to Venezuelan Govt.

built at NBC Shipyards Kure) KURE - GUAM - SINGAPORE - SUEZ CANAL - GIBRALTAR

for bunkers - PORT OF SPAIN/Trinidad - MARACAIBO then dredging Maracaibo channel

____________________________________________________________________________ST

OLYMPIC ROCK/ELYP tanker Greek/Onassis Shipping

Oct - Dec 1960

from lay-up ROTTERDAM/SCHIEDAM - BREST(repairs) - PUNTA CARDON(Amuay

Bay, Venez. ) - BUENOS AIRES

- SANTOS - PUNTA CARDON - BUENOS AIRES

- PUERTO LA CRUZ/Ven - PAULSBORO/NJ

____________________________________________________________________________SS SPRUCE WOODS/ELYP National Bulk Carriers Apr

- May 1961

Bulk Carrier Coal from NORFOLK/VA for YOKOHAMA (via Panama Canal) then KURE for lay-up

____________________________________________________________________________

SS J LOUIS/5MGC National Bulk Carriers

May

1961 - May – 1962

bauxite carrier built NBC shipyards Kure,

Japan chartered to Reynolds Aluminium from KURE - GALVESTON TX (via Panama Canal) for dry-dock - OCHO RIOS/Jamaica- CORPUS

CHRISTI /TX voyages to MIRAGOANE/Haiti and PORT OF SPAIN /Trinidad (bauxite discharge

through conveyor belts

____________________________________________________________________________

SS PETROKURE/ELGE Universe Tankships Tanker

Aug 1962 - Jan 1963

MARCUS HOOK(CHESTER)/PA - PUERTO LA CRUZ/Venez..

- MARCUS HOOK - MENA AL AMADI/Kuwait

- MARCUS HOOK

_________________________________________________________________

CALGARY/ELSC (exCOMMONWEALTH)

Universe Tankships

Jun e 1964 – Jan

1965

Tanker

PONCE/Puerto Rico - PUERTOLACRUZ/Venez. - PONCE - VALETTA/Malta

for

drydock - MENA ALAMADI/Kuwait via SUEZ - DUNKERQUE - MENA AL AMADI - AUGUSTA/Sicily - BANDA SHAPUR/Iran - WILHELMSHAFEN

After 3-1/2 years of service in the US Army, I was “Honorably discharged”

in November of 1952 and settled down in New York to study under the GI Bill of Rights at the RCA Institute, on West 4th Street,

in Greenwich Village. I waited two years for my naturalization. All through that time, while continuing my studies at RCA’s

Institute, I could not get an FCC

license, as an “alien”, nor secure a decent job in the electronics

industry which was contracted for defense work. I was broke and became very lonely and homesick in New York, For the first two months after my discharge,

I went to school during the day and worked evenings as an “assistant” bar tender in a high class restaurant

on East 42nd Street.

During the day, I had to take in electronic and math formulas; Then “coached” by Luigi’,

the restaurant’s bar tender, I had to learn how to blend all kinds of liquors to make Manhattans, Martinis, Alexanders, and other exotic cocktails to satisfy the sophistic clientele of the restaurant.

But my GI Bill of Rights allowance

was not enough to support me. So I worked on many odd jobs during the day: welding

metal saw blades, assembling electronic devices, junior draftsman… attending evening classes until I completed the Radio Telegraph Operator Course. Homesick, lonely, restless, with no secure future, I thought of shipping out on some

vessel taking me back to Europe. By chance in December of 1954, I was directed to a crew

hiring agency on Broad Street in down town Manhattan. The manager’s name was Bodden, he was from the Cayman Islands. I packed a duffel bag with some clothing, books and a toilet kit, put the rest of my belongings into a footlocker, vacated my rented room on West 13th Street in the Village, spent a very noisy night at the Seamen’s Church Institute at the foot of the

Battery where I put my locker into storage in the basement, and reported aboard a Liberty Ship in dry-dock at Hoboken, NJ.

It was cold and rainy in December of 1954. The vessel, the SS Wolverine State (States Marine Lines), was changing her

registry, from US to Liberian Flag and renamed the Orion Trader. I was supposed to be her radio operator. After dry-dock,

she was going to load coal at Norfolk, VA for Naples, Italy. I had not yet a valid radio

license. The captain, therefore, hired a British radio operator and put me in

the crew’s galley as a mess man... The crew was a mixed lot of German, Spanish (the friendliest one’s), Puerto

Ricans and others... a sample of the jobless, homeless drifters one meets on lower Manhattan. I saw that I had put myself into a bind, having

left a secure job for some unknown adventure. For the last six months, while attending night classes at the RCA Institute,

I had worked for a good company and friendly people, bench-testing a new design of ni-cad batteries and doing some drafting.

Now, in the rough and unfriendly environment of my new ship, I was peeling spuds,

washing pots and pans, cleaning mess rooms aboard the wet and cold Orion Trader, in the midst of a miserable, rainy

winter in the Hoboken, New Jersey

dry-dock. But, once again, my “lucky star shone in the darkness”. An

hour before sailing, Bodden, the hiring agency’s manager, came on board, ,

I presumed to collect his fees. He asked me what I was doing in the crew’s

mess. After I told him, he said: ” I hired you out as a Radio operator, not as a crew mess man. You come back ashore

with me and I will get you the job you deserve”. I packed my gear, got my passport back from the pissed-

off captain who had to sail with one man short. Bodden gave

me a ride me back to Manhattan

After another noisy night at the Seamen’s Church Institute, I

took a train for Boston, where I joined the SS Pelops

as radio operator.

She was a tramp, a “Canadian” Liberty

ship, flying a flag of convenience (Liberia),

with a Greek crew. It was my first

“real” job and a turning

point in my life. It gave me a new confidence in myself, and made me proud to

have found a new “profession”.

On December 24th 1954, we sailed from Boston for Rotterdam, loaded with scrap iron. I was fluent with Morse code, knowledgeable

in electronics, but I had to learn from scratch my first job as a ship-board radio operator,

a “Sparks”! I was fortunate to get plenty

of help from many American radio operators, free ‘QSP’ advice on weather schedules and frequencies, traffic lists

and operating procedures. The radio room on the Pelops was located on the bridge behind the chart room. In port, the

smell of fried mutton grease from the galley reached up to the upper decks; the

ship lay under a layer of snow. I covered my equipment with signal flags to protect it from the ambient moisture. The radio

set was an old RCA type; the filament power was turned on with a key, and the emergency gear was a genuine spark transmitter!

I was the only one on board speaking relatively good English. The entire crew was Greek. They were black-haired and shaved

every second or third day. To look like a true sailor, I decided to grow a thin beard. I just had read a book about the Greeks;

they had quite a reputation. Therefore, I locked my cabin at night and wore a pair of pyjamas to bed. But they were a good

bunch, very friendly and did not bother me. The captain’s name was Leonidas Patronas. He kept a canary in its cage and had another pet, a lovely female white Pomeranian “Spitz”. Her name

was Pelops, naturally. Every one

aboard teased and played around with her. I was the only one who treated her as a friend.

I had been raised with a German shepherd when I was a kid, and all my life I have loved dogs with passion. Every time captain Patronas came into the wheel house, Pelops

came into the radio room to lay at my feet and keep me company. The Captain, while standing on the bridge wing, never

bothered to go down to his quarters to relieve himself, he pissed right into

the rain scuppers. Never, in my long seagoing career, did I see any other ship’s captain or crew member do such a thing. I presumed it was a “typically

Greek” custom.

I did not keep

a personal daily log then and cannot remember how long it took us to cross the North Atlantic

through the many severe storms of that winter. It was a long voyage. The normal speed of this type of vessel probably did

not exceed 10 to 11 knots and it appeared that Pelops sailed rather under the high waves than on top. During my first passage,

I got plenty of “on the job training”. There was nobody on board who could help me. I copied weather forecasts

from WSL, WCC, PCH and DAN, listened to their traffic lists, sent and received messages and acquired the habit of keeping

a neat radio log. At the end of my first North Atlantic

crossing, I knew I still had a lot to learn, but I felt confident that I could handle the job.

We arrived

at about 4.00 am at the entrance of the channel leading to Rotterdam.

The Dutch pilot who boarded our ship made a very good impression on me. It was early in the morning, yet his uniform was impeccably

pressed, a black necktie exactly centred on his snowy white shirt. He was freshly shaven, his hands in shiny leather gloves,

his uniform hat squarely set, in a sharp contrast to the unshaven black-haired Greeks...

My parents had not seen me for almost three years. On this cold and snowy winter day of 1955, they traveled by rail

from Metz to Rotterdam. When

they boarded the SS Pelops

they expected to find a clean shaved uniformed ship’s

officer aboard a white ocean liner. I had to shave my new beard of which I was

so proud before they would embrace me! I was disappointed by their reaction,

since for the first time in my life ( I was 32 years already) I had found a job and an environment I really liked. Well, I

thought, tough for them if they could not understand me. I loved my parents very much, I was their only son. But it was time

I became my own counsel, and proceed with my new “career”. We stayed about five or six days discharging our cargo

of scrap iron in Rotterdam. I liked this modern and clean city, already rebuilt after her wartime destruction.

Leaving harbor on ballast, even with a pilot on board, SS Pelops hit a sand bar and twisted her propeller, which obliged

us to proceed to Amsterdam’ s dry-dock for repairs. I did not complain!. I

fell in love with this beautiful city and its friendly people. I toured the canals aboard a sightseeing launch, admired the

magnificent buildings, visited the Reijks (?) Museum where I delighted in Rembrand’s paintings, went to a concert one

evening for a performance of the Amsterdam Gebauw orchestra directed by Eugene Ormandy. I enjoyed spending my evenings in

the intimate smoke filled pubs where I imbibed Holland’s

good beer and many little glasses of Bols Genever. I also passed through Amsterdam’s

less reputable but world-famous streets where “hospitable” ladies sat behind their large windows beckoning for

trade. I took a day trip to the frozen Zuider Zee and the attractive little town of Vollendam.

After a week in dry-dock, we crossed the North Atlantic from East to West bound for New

York. In ballast this time, the old ship pitched and rolled through many more winter storms, until

she dropped anchor off Staten Island on a cold but clear day at the end of February 1955.

I left the SS PELOPS, eager for new adventures, other ships, other horizons.

PART TWO

II - SAILING FOR LUDWIG

I paid off the SS Pelops after she dropped anchor

near Staten Island on her return from Amsterdam. Stepping ashore from the Ferry on Lower Manhattan, I spent

another noisy night at the Battery’s Seamen’s Institute. The next day, I rented

a small furnished room in the upper West 70’s and spent my days at the Seamen’s Institute and other sailor hangouts

searching for a new job. One day I called at the offices of National Bulk Carriers on Madison Avenue. I was well received

by the licensed personnel manager, Mr. Southwell. He told me to wait until called for a berth aboard a tanker sailing to Sumatra. Meanwhile, he issued me for $ 5.00, and a passport photo a Panamanian radio operator’s

license (“Certificado de Idoneidad”). For a few days after that, I read up on Indonesia at the New York Public Library on 42nd Street.

At the beginning of April, Mr. Southwell called me to his

office. He gave me a letter of introduction to the master of the SS Petroqueen and a TWA tourist class ticket for San Francisco. At my arrival,

the company’s agents, Ahern and Co. (their offices were on Sansome Street)

put me up for one night at the YMCA near the Ferry Building. The next morning, a launch brought me, with the new chief mate, Mr. Gerhard

Krause from Hamburg, out to our new ship, the tanker SS Petroqueen, anchored in the

bay, awaiting a berth at the Standard Oil refinery in Richmond. The Radio Officer whom I replaced was a taciturn middle-aged American who did not

share my enthusiasm for my new job. His explanations were rather brief, he was in hurry to disembark. But this time it was

easier for me, I did not have to learn everything from the beginning. The small and narrow radio room was on the port-aft

side of the main deck. The radio equipment consisted of an RCA 5-U console. Its power supply had rectifier tubes instead of

a motor-generator. The equipment was in good shape, and the station well supplied with spares, tools and office supplies.

Together with my duties as Radio Operator, I had to take care of all the office

work: typing the crew's and customs

lists, ship’s articles, payrolls, crew allotments etc. I had to check the

crew’s passports and their vaccination certificates. It was a tedious task done

on the old radio room typewriter, the “mill”. There were no Xerox copying machines nor computers in 1955. But

I set to it willingly. It took two days for the ship to discharge her cargo of Sumatra crude

oil into the Richmond Standard Oil Refinery tanks, during which I familiarized myself with my

new surroundings. The Petroqueen was a tanker of approximately 35,000

dead weight tons, built in 1953 in Kure, Japan.

D. K. Ludwig, the American shipping magnate, had leased the shipyards of the former Imperial Navy at Kure, where all the great Japanese aircraft carriers and battleships, like the Yamato, had

been built. It was situated on the shores of the Inland Sea, near Hiroshima. Ludwig’s ships‘ construction was straight forward without any frills or attention to the crew’s

comfort nor to appearance. (his motto was: “If it doesn’t carry any oil, we don’t need it...”) The

smokestack was just that, a straight black pipe. There was no insulation inside the steel bulkheads, nor any air conditioning.

But the ship was freshly

|

|

| RADIO CONSUL - "PETROQUEEN" |

painted.

The accommodations were clean and well cared for. My cabin, in the mid-ship house on the port side of the main deck, just

behind the radio room, was a little confined, with a bunk, a settee with drawers, a small wardrobe and a wash - basin. I had

to share the heads and showers with the 2nd and 3rd mates. The Chief Mate’s cabin and office faced forward of the midship

house. He had his own bathroom and head. The Captain’s stateroom and office, the slop chest and the owners cabin were

on the deck above. Then there was the wheelhouse, the chart and gyro rooms. In the aft accommodations where the engineers

and crew quarters, the galley and mess halls, and the large engine room with its steam turbine which could drive the ship

at a maximum speed of 17 knots (the captain usually maintained her at an economic 14 to 15 knots). The chow was tasty and

plentiful. The unlicensed crew came from the Cayman Islands which were still British territory, in the Caribbean between Cuba and

Jamaica. Their names were Bodden, Mclaughlin,

Ebanks... Bill Braud the chief engineer came from New Orleans;

those who did not know him thought he had a rough and tough personality. He reminded me of Wallace Berry, the movie actor

from the ‘thirties, with his right eye half-closed, his many colorful tattoos on his chest and arms. But he really was a very nice friendly person, a good shipmate

who ran an efficient engine room. It was so clean you could have eaten on the deck plates. It reminded me of a Dutch tugboat

I had visited in Rotterdam. The Chief was a “ham”,

a radio amateur. He had his transceiver in his office and had set up an antenna with

a six-element rotary beam antenna on the cargo mast on top of the after house. He was a great help to me and we got along

splendidly. He always inquired of my watch schedule so as not to interfere with my radio reception, when he wanted to transmit,

and I always advised him when I had traffic to handle or weather forecasts to receive.

We left Richmond on the afternoon

of April 12t 1955, passing under the Golden Gate Bridge. The weather was pleasant as we proceeded along the California

Coast, bound for San Pedro, there to

load refined petroleum products for Kanokawa, near Kure, Japan. The crew had a distasteful job to do before the tanker could load its new

cargo at San Pedro. All the tanks had to be thoroughly cleaned. First, steam pipes for the Butterworth machines were fitted

into the tank openings on deck, which then were cleaned with live high-pressure steam. When they were free of gas, the crew

had to climb down vertical iron ladders into the cargo tanks and muck up into buckets the thick petroleum residue on the bottoms,

the sides, in every corner of the huge deep steel caves. On deck, other seamen hoisted the buckets on ropes and emptied them

overboard into the sea. In those times, we knew nothing about ecology and the

protection of the environment, we had never heard of Captain Cousteau, no special containers existed yet aboard vessels to

store petroleum wastes.

San Pedro in the mid-fifties was still a lively sailor’s

town with many taverns and shops. After a day and a half of loading we put back to sea, on a Northwesterly course.

Before departure,

I hadcopied the weather forecasts broadcast from all the "Pacific Rim" radio stations: San Francisco,

Vancouver, Guam, Honolulu, Tokyo. On my first voyage, our skipper wanted

to take the shorter Great Circle route to Japan,

despite the risk of rough weather along the way. It did not fail. As expected, at about 49 degrees of latitude North, we met

several vicious gales which smashed our starboard lifeboat. The Captain was relieved

when we returned to San Francisco.

Our new Skipper, John Parker, was a young, active and very

intelligent gentleman from Philadelphia

who had a University degree in Marine Engineering. He kept a tight, clean ship. Parker was very "safety conscious". We had

to walk along the cat-walk to the aft accommodations for our meals or for any other reason. When the weather was rough, he

ordered a temporary change of course to protect all personnel from wind and waves. With Gerhard Krause the chief mate and

Bill Braud, the Chief engineer, we had a very good crew, the Petroqueen became

a "happy ship". There was plenty of overtime for the unlicensed deck and engine men. The Chief Engineer spent most of his

time at his ham set, chatting with radio amateurs all around the Pacific and on

board other ships, “Maritime Mobile” ham stations, but the engine room was clean and efficiently run. His was

a "colorful" personality: “... This is W6KXX, Mobile Maritime...the Tanker Petroqueen, in the Pacific....Hello,

old friend, how nice to talk with you again, a real pleasure...” then he would turn around, and, while his correspondent

answered him, he would wink to us and grumble “... what a pain in the ...,

that old s. o. b., that old f...”, with the transmitter cut off. He would come back on the air, and resume his “friendly”

conversation, with the nicest and kindest of compliments and expressions of his deepest friendship. But he carefully cut off

his transmitter whenever he expressed his thoughts with the strongest expletives. Every third or fourth day, if the weather

was good, Captain Parker and myself helped him to take down his 6-element rotating beam antenna, on the roof of the after-house

and put it back up again on the cargo mast after he modified his designs. My

friend Joe Prewitt told me that, when he was a teen-ager ham operator, he used to contact him aboard the “Tanker

Petroqueen, Maritime Mobile in the Pacific...”

The deck hands spent their

time chipping rust and painting decks and bulkheads. As soon as the last paint job was done on the poop there started a new

one on the forepeak. The engine - room crew maintained the steam turbines and the deck machinery: anchor windlasses, steam

winches, cargo pumps. The crew looked eagerly forward to their shore leave in Japan.

We usually stayed two to three days in Kawasaki or Kobe,

which was our favorite liberty port. The chief mate and the captain managed to find excuses for slowing the discharge of our

refined cargo. On my first voyage, we called at Kanokawa, on a small island in the Inland Sea near Kure where the Petroqueen had been built. I enjoyed my visits to Japan. In the mid-fifties; the US Dollar was worth 360 Yen.

We found the cost of living and prices of goods very affordable compared to the United

States. And we especially appreciated the beauty and gentleness of the Japanese women. Many

love affairs were born. I never spent a lonely night ashore in Japan.

As a Radio Operator (the “Sparks”) I was “the

first one ashore, the last one back on board”. But since I was purser and in charge of the payroll, I had to return

during the day aboard ship to issue more cash advances to the crew. I spent my

time in Tokyo, on the Ginza during the day and the early evening hours: Shopping in the large department stores, taking a “Turkish bath” in the specialized establishments, where a lovely attendant took good care of me ((bath and massage), viewing a show at the Nishigekki Music

Hall, or at the Kabuki theater. Behind the Shinjuku railroad station were little narrow streets with small restaurants where

I had many delicious sushi dinners, and little bars where I befriended the charming

“hostesses” who, sometimes, became my lovers for a night. I also took numerous sightseeing trips to the

country side. Once I traveled south to admire the great Buddha of Kamakura. Another

time, I went to Lake Hakone at the foot

of Mount Fuji. Some evenings a taxi brought me to a certain address near the Sumida River: It was a beautiful house, entirely

built of wood in the traditional Japanese style. In the entrance hall, an elderly lady, the hostess, greeted me with deep bows. I tool off my shoes, and was lead into a small room with thick rice straw mats

(called “tatamis”) and cushions on the floor. The financial transaction were simple and straight forward. I was

to get acquainted later with the so-called “red light” section of many Japanese cities. As long as these were

preserved from Western (American) influence, there was none of the sordid notion of prostitution, of raw commercial “sex”

as one is familiar with in the “West”. The Japanese architecture, its interior decoration, retained a delicate

beauty in its sober elegance. The girls were not the traditional Geishas, but were no less delicate, sweet and devoted to

your needs and desires. Sometimes, I met some “ladies” who had been spoiled by American GI's; believing they would

please me, they affected the “Yankee” style of speech and behavior. Our relationship rapidly came to an end and

I searched for a Japanese companion behaving in a more traditional fashion.

In the house near the

Sumida river… the hostess presented me, with deep bows, a cup of hot green

tea and small rice cakes, and left. I felt at ease, relaxed in this quiet environment. The Japanese style inspired in me a

state of peace and serenity... A few minutes later, the sliding door opened, a beautiful and graceful young lady dressed in

a colored silken kimono knelt before me: “Kombawa..”. It was my chosen companion for a night of love. Together

we took the honorable O’Furo, the Japanese bath. We undressed each other with no false shyness. There was no shame,

everything appeared natural. She soaped and rinsed me all over, I did the same for her, and when there was no more soap on

our bodies, we bathed together in the tub of almost boiling water. I felt clean, relaxed, serene, and spent a night of delightful

love with this sweet young lady. With time, I began to appreciate Japan

and its people; I became interested in its culture and read many books on Japanese history, literature and art.

After discharging our

cargo at Kawasaki, the Petroqueen proceeded on a southwesterly course, along the Ryu Kyu Islands.

If there was no threatening typhoon moving to the West we took a shortcut to the South China Sea by transiting the Surigao Straits and the Sulu Sea.

There was no air-conditioning aboard Ludwig’s tankers, and one can easily imagine how it felt sailing through those

Southern latitudes. But I enjoyed watching the flying fish and the occasional

dolphins jumping out of the clear deep blue waters and playing in our bow waves. Ferocious sea battles had beene fought during

WW II in the San Bernardino and Surigao passages. But now tere was only “pure enchantment of the Tropics”…

We entered the South China Sea through the Balabac straits, and sailed along the coast of Borneo.

Heavy, sweet vegetal smells arose from the tropical rain forest, dark thunder clouds hovered over the jungle, lightning bolts

flashed inland. In the evening, flights of “flying foxes”, huge bats,

glided over the land. We rounded Singapore,

leaving to starboard the elegant silhouette of Raffle’s Lighthouse framed by palm trees. Steaming by the many small

islands around the Southern tip of the Malaysia Peninsula, we encountered countless vessels of all kinds, sizes and nationalities. Approximately

100 miles into the Straits of Malacca, our ship sailed up the Bengkalis river, and docked at a clearing in the Sumatra jungle. It was the Sungai Pakning terminal of the Caltex Oil Company. Small river tankers brought

the crude oil from the drilling fields up river and pumped it into large oil tanks, from which it was loaded into the tankers

from Norway and elsewhere. Universe Tankships

Inc. (National Bulk Carriers) had a charter contract with Caltex and Standard Oil of California. The officers aboard the river

tankers and the managers of the terminal, were Dutch. They were wonderful fellows and I had many friends among them. All ships’

officers had a standing invitation to the club ashore, and we always got a warm welcome. I passed enjoyable days there with

my new friends, playing ping pong or billiards, sipping Heineken beer, invited

to delicious lunches of curry and other Indonesian rice dishes. On Christmas day of 1955, a large sign at the club’s

entrance “requested guests to leave their skis and boots outside”. The owner of the grocery store and restaurant

in the Indonesian village nearby was Chinese. He exchanged our US Dollars for

Indonesian Rupees. His was a large family, and his wife seemed to be in a permanent state of pregnancy.

I spent fourteen happy

month aboard the Petroqueen. I enjoyed my job and I got along very well with everyone aboard. Gerhard Krause was from Hamburg. I was French, had fought against the Germans during WW II

in the French Resistance. But right from the first day on, we agreed never to

speak in German while on board nor to mention any of our countries’s old problems. Mr. Krause was a Seaman of the “Old

School” and a Gentleman. I

came to admire, to respect and to like him very much and we became good friends. Later, he would be my Captain on another

of D. K. Ludwig’s ship (the bauxite carrtier J. LOUIS. ) I remember

two memorable shore parties with him. During a rainy month of November, 1955, the Petroqueen went to dry-dock for five

days at the Hunter’s Point shipyards in San Francisco.

One evening, Mr. Krause and I went “out on the town”: We had diner at an elegant French restaurant and, after

some “pub crawling” through the International Settlement, we finished the night at the Montmartre,

a French night club on Broadway. On other evenings, we enjoyed a more classical form of entertainment at the Bocche Ball,

on the corner of Columbus and Broadway, an Italian night club specializing in Opera singing.

In February of 1956, Gerhard Krause managed to get away from supervising our ship’s discharge and we spent a

beautiful night in Yokohama, in a typical Japanese inn, each

of us with a lovely companion.

Like the other tankers,

ore-carriers and dredges of National Bulk Carriers and Universe Tankships Inc., the Petroqueen sailed under the flag of convenience of the Republic

of Liberia, her home port Monrovia. D. K. Ludwig was assumed to be the richest man in the United States. But he shunned publicity and avoided the press; he did not belong

to the “Jet set” society like his Greek rivals. Not much was known about his private life. Despite his great fortune,

rumor had it that he traveled by commercial plane, not even in business class. Later, in the seventies and eighties, he had a huge floating paper mill built in Japan.

Tugboats towed it half around the world to the province of Jari

on the Amazon river in Brazil, where he had bought a piece of land as large

as the state of Connecticut. On it he wanted to plant a

special kind of pine tree. The mill would convert their wood into paper pulp. But the project proved to be an ecological disaster.

The military dictators who ruled Brazil

did not like the idea of a foreigner owning so much land in their own country and they expropriated him. He lost huge amounts

of money in his latest venture

The vessels of Universe

Tankships Inc. were efficiently run, well maintained, well supplied, with an emphasis on safety. At that period, most of the

company’s Captains and Chief Engineers were Americans. Other officers were

from Germany, Scandinavia

(my best friends were the Danes), Great Britain, the Netherlands, they

were Greeks, Italians, Yugoslav. I only once I met another Frenchman aboard a Liberian ship, but this, as Rudyard Kipling

used to say, “is another story”. In 1956 my wages as Radio Officer and Purser were approximately $ 250 per month

including overtime, with 15 days paid vacation a year. A voyage from San Francisco to Sungai Pakning via San Pedro, Kawasaki and back took about

60 days. We generally managed to avoid the many Pacific winter storms, because

we stayed South of 40 latitude North on our way to Yokohama.

Copying the available weather forecasts along our path I looked out in particular for tropical storm and typhoon warnings.

Captain Parker carefully routed our ship around or away from their paths.

One day, there was some

ill temper between the Chief Mate and the steward. Gerhard Krause left the choice

to the Captain. Either he, or the steward would leave the ship. When we returned to San

Francisco, the steward together with his young friend (?), the

cabin boy, were paid off. We got a new steward and a new BR.

(bed room messman). It resulted in a tremendous improvement in the taste of our

chow and the cleaning and upkeep of our cabins.

I had become proficient

with my duties as a Radio Officer and ship’s purser. I came to recognize the dangers of typhoons and severe storms of the Pacific Ocean, the dense fogs along California’s

coast; I knew the joys of sailing along tropical islands, the magnificence of sunsets, the inspiration of sunrises. And I

fully took advantages of all the pleasures of land, during my shore leaves. But when ever after a lengthy stay in port we put back to sea, we all had the same feeling of being cleansed, of being “purified” of all the vileness of the land (on board Navy ships, it was:”… Now hear this, clean sweep down fore to aft…”),

I have made three lists of Captains under whom I have sailed. On the first list, are those who left me indifferent.

They did not bother me, I performed my duties, they did theirs, we had no complaints

about each other. On the second one I listed the s… heads, the stupid ones, the mean b…, those who did not

like me. Luckily this list is a short one. On the third were listed the very

good ones. Theirs was always a happy and lucky ship, safe and efficiently run, like the Petroqueen under John Parker’s

command. How can I forget the big Christmas party he gave for the Officers and Crew

in Yokohama on

December 25th 1955?

He was most helpful to

me in my job as “purser”, with payroll work and ships articles. He let me use his personal electric typewriter

in his office. When we entered Japanese ports, about a dozen uniformed officials came aboard: There were always two or three

officers for each function: immigration, customs, public health. In separate folders, I brought crew lists, crew customs declarations

(how many cartons of cigarettes, bottles of liquor, phonographs, cameras etc...

), the crew’s vaccination certificates and passports. The Japanese were dressed in sharply creased uniforms, wearing

white gloves, their shirts freshly laundered, diffusing a clean smell of soap. Then came on board the gentlemen of Sharp and

Co. Ltd., the Company’s agents in the Far East, who brought our mail and thick bundles

of Japanese currency. It was one of my duties to give a draw to the crew. The boys had

to sign a list of their draw in triplicate, and this sum was then deducted from their wages at the end of the voyage .

As much as I enjoyed my shore leaves in Japan, with no less pleasure

did I look forward to our return to San Francisco. I never

missed our passage by day or by night under the beautiful Golden Gate

Bridge, it always thrilled

me. The San Francisco Pilot Boat had a sail. In the spring of 1956. On one of our approaches to the Bay entrance, the lifting

fog revealed a school of small whales alongside our ship. Ahern and Co. were our agents on

the US West Coast, and they were very good to us. Even before we dropped anchor

at the quarantine station off the Ferry Building,

while sailing along the Marina and Fort

Mason, and before the ship was cleared by immigration and health services,

a launch left the shore and came alongside carrying several US Mail bags for

us. I brought them to the radio room, where I sorted the ships mail. I distributed

the official envelopes to the different department heads, and brought the personal letters and packages to the officer’s

staterooms, the crew mess or even down to the engine room. After docking at Richmond’s Standard Oil pier, when all the ships paperwork was taken care off, when all of us were paid off and Captain Parker had given me his OK, Captain Miller, the port agent took me ashore with him to my beloved City of San Francisco. I usually went

shopping at the City of Paris on Union Square, dined in an elegant French restaurant, went "pub-crawling" in the International

Settlement, or saw the latest French movie.

I corresponded regularly

with my parents in France. From the Pacific

and China Sea, I was able to contact FFL - St.

Lys Radio, the powerful French marine radio station, through which I sent them our next ports of destination and approximate

dates of arrival. They sometimes sent me my hometown newspaper, the “Républicain Lorrain”. One day, I wanted to have some fun. I took the newspaper ashore with me to Tokyo. At a newsstand, I slipped it in-between the local press like the Asahi Shimbun and

others, all printed in Japanese characters. I took some photographs. Then again in Sungai Pakning, among huts and palm trees,

right in front of the local Communist Party headquarters, I gave the newspaper to a few young men who made as if they were

reading it. I went to visit the Hindu tailor of the village, a venerable gentleman with a long white beard and a large turban

on his head. He also spread the news paper in front of him. I then sent the prints to the Républican Lorrain with a caption:

”A citizen of Metz traveling in the Far East was immensely pleased to see that your newspaper is read also on the other

side of the world...” They published the photographs with my letter. My parents knew it was one of my funny tricks and

they had a good laugh.

A painter came aboard

one day in Yokohama to sell paintings of our vessel on silk. I bought one and sent it to my parents. They had it framed and

hung up in their living room. After they passed away, this picture followed me

from France to New York, to California, to France and back again to Belmont.

It is very dear to me.

In July

of 1956, after 14 very pleasant and satisfying months aboard the good old Petroqueen, I needed a vacation,

it was time for a change. I was paid off in San Francisco on June 28th 1956.

The Company had authorized me to travel back to Japan aboard the Petroqueen,

this time as a passenger. With my discharge certificate, Mr. Parker gave me a letter of recommendation for my next Captain.

At the end of my vacation, I was to join on her completion in Kure, Japan, the Universe Leader of 85000 dead weight

tons. She was to be, in 1956 The largest tanker in the world.

PART THREE

from my personal files

The SAN FRANCISCO CHRONICLE, Wednesday,

November 14, 1956

WORLD’S BIGGEST SHIP HERE

New Vessel Brings Record Oil Cargo

by Jack

Folsie

The visitor is the Universe

Leader - a tanker - American owned, Japanese built, flying the flag of the African

Republic of Liberia and under

contract to Standard Oil Co. of California. On her maiden

voyage, she carried Sumatra crude oil from the South Pacific to make enough gasoline to run every one of California’s 6,000,000 autos for 50 miles.

Low in the water with

her record oil cargo, the tanker glided in through the Golden Gate shortly after 6 a.m. dwarfing

two outbound aircraft carriers. She had waited overnight outside the Golden Gate for a high

tide so she could safely enter. Even so, she cleared the San Francisco

sand bar by only about four feet. The giant vessel dropped one of her 16 ton anchors to hold her steady against the quiet

tide and proceeded to wait for the first of several operations needed to pump out her cargo. The super tanker is so deep in

the water - her keel is 45 feet under the surface - that loads of oil must first be pumped out of the giant. Only after this

lightening can the Universe Leader proceed, about Thursday, to Standard’ long wharf at Richmond to complete her unloading. In 52 separate tanks below deck .the ship carried 602,622 barrels or 26,000,000 gallons of black sticky oil. This is enough oil to keep the

Richmond refinery going full speed for four days. The liquid

cargo with the weight of the ship displaces 109,000 tons of water. The tanker’s

dead weight tonnage. is 85,500 tons. Her nearest rival, the Queen Elisabeth, is 84,000 dead weight tons. “You can compare

that with your giant aircraft carrier Forrestal” said Chief Mate Bernard J. Baum. “The Forrestal displaces only

75,000 tons”.

This $8 million jumbo is the responsibility of Captain Jesse F. Bird, a 60 year old

New Yorker. He predicted that his ship, one of the new breed of tankers that

can’t fit in the Suez Canal, will be just a has-been for size. The Universe Leader is owned by National Bulk Carriers Inc. of New York

which registered the ship at Monrovia, Liberia,

a home port the tanker is unlikely ever to visit. Liberian registry, however, allows the company to take advantage of liberal

maritime and tax laws enabling the ship to compete with other foreign flag tankers. The crew consists of 58 men of six nationalities

including American officers, a French radio operator, and German, British West Indian, Chinese and Okinawan crew men. “Everything

is big around here, but the men”, said chief officer Baum, grinning. “We are just human”.

There were some crew changes on our arrival in San Francisco, when I was paid-off on June 28th. My replacement was a young, and cheerful Dutchman who had brought his guitar along. Mr. Krause went back

to Hamburg for a well deserved vacation, and the young American third mate from Upstate New

York, a graduated from the Kings Point

Merchant Marine Academy

was promoted to Chief Mate by Captain Parker. The second mate was a grouchy old Canadian Irishman. I moved into the owner’s

cabin on the Captain’s deck, as a “passenger”.

This was

to be a cheerful voyage. The weather all along our Westerly route, just South of the 40th

parallel, was perfect. Before departure, I had bought a case of French champagne

at the City of Paris, the great department store on Union Square (replaced by Neimann & Marcus). Captain Parker

still had a provision of exquisite Japanese caviar. In the evening, after the 4

to 8 p.m. watch, we sat on the main deck watching the sun set in the West. The Dutch radio officer would fetch his guitar

and sing sea-chanteys, cow-boy songs or popular tunes, while Captain Parker and I served champagne, crackers and caviar. We were happy, care-free, it felt good

to be at sea, on a good ship, with good men.

Meanwhile, in the North Atlantic near the Nantucket Lightship, the SS Stockholm

collided with the Italian liner Andrea Doria. The French Line’s Ile de France made a 180 degree turn to rescue the passengers of the sinking Italian vessel. In the Middle East, Nasser, the

Egyptian dictator, nationalized the Suez Canal, and a new world crisis was born.

In Yokohama, after saying good-byes to my Captain and

shipmates, I obtained a two-month tourist visa with my French passport. I took a taxi to Tokyo

and stayed overnight at the Kokusai International Hotel, behind the main railway

station. But I wanted to get away from the big city. A very humid heat wave had

settled over Tokyo to make my stay unpleasant. I shipped my sea bags by rail to Kobe and flew to Osaka by Japan Air Lines the next day. I had a lady-friend in Kobe. Her sister was married to an innkeeper near the ancient capital city of Nara,

between Kobe and Kyoto. I settled

down at this lovely hotel, adjusting myself to the local customs. I slept on

a rice straw mat, the “tatami”, ate with chop-sticks the food I was

served. A “western-style” toilet on the premises, was my only concession to "western" customs. I was happy with the Japanese way of life. My hosts were delightful

and treated me with much friendliness. There were many things to see; I went to

Nara to admire the huge statue of Buddha, to feed the tame

deer roaming freely in the park among the many temples and stately pine trees. I felt in peace and harmony with my surroundings.

In beautiful Kyoto,

one evening in a bar I met three Australian wool merchants. We had a big party, and I over-indulged with beer and sake. Trying

to jump over a low fence, I twisted my right ankle. In a minute it had swollen

to the size of a grapefruit. A taxi brought me back to my hotel in the country

side. The next day, my host called a doctor who prescribed hot humid bandages and complete rest. To overcome my frustration

and loneliness, the owner’s wife asked her sister, my lady friend in Kobe, to stay with me until I would be fit again. She gave me much tender

love and care. My injured foot was healing fast .and soon I was able to walk with a cane. I said “Sayonara” to

my love and to my friends. I had read James Michener’ novel, “Sayonara” (Hollywood made a very bad movie from the book) and I wanted to visit the resort town where

Marlon Brando, in the film, had met his lover. In Osaka, a

special train took me to Takarazuka. It had been built around a large music hall, whose performers were all women, in contrast

to the traditional "men only" Kabuki theater. It was a kind of Japanese style “Radio

City Music Hall” with

traditional Japanese and "western style" musicals and dances on a large stage. The women in the shows were lovely, the little

city was pleasant,. Then I returned to Kyoto, to celebrate my birthday with my lady friend on the 8th of

August,.

Towards the end of the month, I traveled south to the port city of Kure,

where my new ship was being built. It had been the main naval base of the Japanese Imperial Navy (what Norfolk

and San Diego were for the American, Brest and Toulon for the French Navies). The big battleships like the Yamato and the Japanese aircraft carriers of WW II , which had bombed Pearl

Harbour, had been built there. Daniel K. Ludwig, the American shipping

"tycoon" leased the big yards and started to built his own ships. Now the construction of the largest tanker in the world,

the Universe Leader was underway.

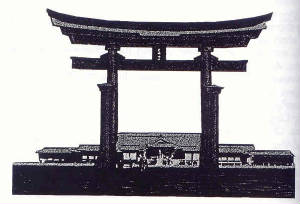

Kure lies on the shores of the lovely Inland Sea, across from the island shrine of Myia

Jima, about 15 to 20 kilometers

from Hiroshima. Since the ship would be finished in September,

I continued to “play the tourist”. I traveled by ferry boat to the famous hot spring resort of Beppu, on Kyushu Island. Famous for the ponds of boiling yellow sulfur mud springs - smelling like rotten eggs. I stayed at a charming Japanese inn on the outskirts of the town. The inn’s

owner had been employed before the war at the Japanese consulate in Hamburg.

There was no language barrier this time since we both spoke German. He treated

me like a “honored guest” and offered his special sake. In the evening,

he had a taxi bring to my room the loveliest host of the local “geisha (!?!) house”. I spent two memorable nights

at my new friend’s lodge. From Beppu, I continued, by train to the Mount Aso volcano, which I ascended on the back of a donkey.. Evil smelling vapors rose from the crater’s

depths. Then I traveled to Nagasaki where I was received with

“full honors” (French champagne, a steak diner) by the Honorable Consul of France. He was a retired French colonial

civil servant who had lived many years in French Indo China, and had settled

in Japan for his retirement. Nagasaki had been rebuilt after its destruction

in August of 1945. I visited the house on a hill overlooking the bay, where Madame Butterfly was assumed to have waved her

good by’s to her lover’s ship...

Puccini made a beautiful opera of this love story.

On my return from the island of Kyushu,

I stayed a few days in Hiroshima. It was another city which

became dear to me. There was a special atmosphere of “Peace on the World”, of "Universal Friendship" in Hiroshima, I visited the

Peace Memorial and the museum with all the reminiscences of that fateful August day of 1945... There was a popular music festival

at Hiroshima’s International Hotel, and one day a group

of Japanese teen-agers mistakenly thought I was a French singer and asked for my autograph. I graciously obliged, and I had

big laugh, at the kid's expense! Hatsuko Kawamoto was the receptionist at the Japanese-style hotel where I stayed. We became

lovers. Together, we traveled to Miya Jima, the Holy Shrine on a small island near Shikoku. Another time, we stayed three days at a hotel in the mountains. There was a small

stream of hot water, where all the guest bathed in the nude, without false shame or modesty.

But it was time to return to Kure,

and see for myself how a big ship was being built. All the licensed officers of Ludwig’s

ships resided at the Senba Hotel before sailing. I met Jesse Bird, the “commodore” of the N. B. C. fleet. He was

a real old timer, certainly closer to 70 than to the 60 years he declared on the crew list.

He had been around Cape Horn in sailing ships.

He commanded, on their maiden voyages, all the new ships built at the

N B C Shipyard. And there was also Borje Borjeson, the Big Swede, who was the company’s Port Steward. I was the first

of the crew to arrive.

I did not get bored in Kure.

I became interested in ship-construction, and did a lot of “pub-crawling” in the town's "red light" district.

From a photo shop I rented an enlarger and developing material to process and print my own photographs. And every second or

third day, I took the train or bus to Hiroshima to meet my

beloved Hatsuko-san; On other days, she took the last train of the evening after her work to join me at the Senba Hotel.

The Allied occupation of Japan

was in its last stages. The Kure zone had been allocated to

the U.K. Armed Forces and a small British army detachment was stationed there. Completed at the beginning of September, the Universe Leader was scheduled

for her sea trials. The British

officers of the Kure

garrison were invited aboard. I was busy in the radio room with the ship yard electronics engineers who tested the navigation

and communications equipment. I learned a lot, watching how the compasses were

swung, the radio direction finder calibrated, the transmitters and receivers tuned-up, the auto-alarm system and the battery

charger tested. The radio equipment was the latest RCA model 6-U radio console. The vessel’s sailing and engine performances

were in accordance with the required A.B.S. specifications. The shipyard managers, Universe Tankship's Port Captains and engineers,

Captains Jesse Bird, and Peter McGuire, John Rawles, the Ched Engineer, every one was satisfied with the new vessel's performance.

For the British officers the sea trials where the occasion for a big party; they could not have cared less for the Universe

Leaser's sea worthiness. They had brought

on board with them cases of whiskey, gin and beer. I was not invited to the party. But what pissed me off, was that

they took all the booze which they had not consumed back ashore with them, even half empty bottles. Stick under their arm, stiff upper lip, “ I say, old chap, jolly good show...” and all that...

Typically British?

Then the new crew arrived: Chief Mate Joe Baum, the steward, mates and engineering officers.. , The deck and engine

unlicensed men were a blend of Cayman Islanders and Japanese from Okinawa. The Cayman Islanders,

excellent seamen, where soft spoken,. friendly, never a source of trouble. Unfortunately their worked at a slower and more

relaxed rhythm that the Japanese from Okinawa. The Cayman Islanders’ nonchalance and

casualness would cause friction with the Okinawans, and later NBC’s personnel manager would man the ships with a more homogeneous crew.

Captain Litchfield, the Port Captain from New York,

joined us the day before departure. The largest tanker in the world was to sail on her maiden voyage. It would be a “first” in Maritime History.

That night there was a big party at the Senba Hotel. After a delicious diner of Kobe Beefsteak and O’Suchi, there was much rejoicing, singing, dancing

with the ladies of the Hotel. There were unlimited quantities of beer, sake and even a few quarts of Suntory whisky, smooth like aged Scotch… The party at the hotel broke

up around 10:30 p.m., but Chief Mate Baum, the young German steward, the 3rd mate and 3rd engineer, both from Hamburg and

myself, all of us dressed in the hotel’s house kimonos, Japanese wooden slippers (gettas) on our feet, made a last round of the neighboring bars to say good by to our many lady friends. Hatsuko Kawamoto took

a late evening train from Hiroshima and joined me in my room

for a last night of love. She came with us in the taxi who took us around

six a.m. to the pier, where we boarded the SS Universe Leader for her maiden voyage.

The weather was pleasant, a light swell welcomed us into the Pacific after our passage through the Bungo Suido straits

separating the Islands of Shikoku and Kyushu.

We were bound for Singapore

for bunkers. Captain Jesse Bird assumed command, assisted by Captain Pete McGuire who would take over as Master when Jesse

Bird would leave us in the United States.

McGuire was a very friendly Irishman from Boston, and a magnificent "Master Mariner". He

had been a pilot of the Suez Canal and told us many stories about his experiences. We were

particularly interested since Nasser's of Egypt take-over of the Suez Canal had created an ugly world crisis. The size of the Universe

Leader would not permit her to transit through Suez.

She introduced the era of the Super Tankers. They would bring Middle East crude oil to Europe and the United States the long way around the Cape of Good Hope.

We sailed along the Ryu Kyu Islands

and passed the Formosa Straight into the South China Sea. A few days later, we docked at Keppel’s Harbor in Singapore to take bunkers. There were also other kind of provisions brought aboard:

columns of coolies, ascended the accommodation ladder, carrying on their back cases of beer, gin, whisky, and other kinds

of alcoholic refreshments, Coca Cola, soda, Schweppes tonic water etc. Captain Bird had decided as a gesture of public relations

to open the ship to visitors. He detailed the steward and myself near the big

icebox in the mid-ship house to serve drinks to the many visitors, what ever

they asked for. To the Hindus, Malays and Chinese, Coca Cola, Pepsi or iced soda water. To Englishmen, Australians, Americans

or other Westerners, beer, gin, whiskey or what ever. And since it was very hot

in Singapore, and the ship’s quarters

not being air-conditioned, we ourselves became very thirsty. When I finally managed to get ashore after the party, I was unsteady on my feet and suffered from a headache. A Chinese lady I met at Singapore's "Great World" invited me to her home. She lightly spread some Tiger

Balm on my forehead, which relieved my headache and allowed me to fully enjoy her company.

It was autumn, there were no typhoon

warnings. But other alarming happenings were threatening the world's peace: British and French amphibious forces had landed

near Port Said, Egypt to take the Suez Canal

back from Nasser. The Soviet Army brutally suppressed a revolt in Budapest,

and President Eisenhower, probably intimidated by the Russians' saber rattling, ordered the Anglo-French Expeditionary Forces

out of Egypt. The French Forces had given

the Egyptians a thorough beating near Port Said, and were approaching Cairo. The Israelis were victorious in the Sinai Peninsula, but the unfortunate pull out

of the French and British from Egypt made the whole affair appear like

a big triumph for Egypt’s Nasser.

We

dropped anchor off Sungai Pakning, on the East Coast of Sumatra, I met old friends.

Again, Jesse Bird gave a few parties

on the big ship for the staff of the oil terminal. It took six days, and many loads of river tankers to fill our huge ship with close to 500,000 barrels of

Sumatra Crude Oil. I wrote to my parents: ”... It was like filling a bath tub with a tea kettle..."

The Universe Leader encountered

“no significant weather” on her Eastbound passage of the Pacific. The typhoon season was over. We settled pleasantly in our new ship’s routine. The radio room and adjacent stateroom were spacious

and comfortable, although there was still no air-conditioning aboard Ludwig’s big ships. The radio equipment worked

well and did not give me any problems. I communicated with all the familiar coast radio stations on the “Pacific Rim”, copying conscientiously all available weather forecasts and sending faithfully the

ship’s observer messages to the US Weather Bureau. As “purser”, in charge of all paper work, I was kept

busy typing on the radio room's “mill” three or four copies of crew and

customs, payroll and allotment lists, the ship’s articles, checking passports and vaccination certificates.

I was also in charge of the ship's slop chest. Borje Borjeson, the Company’s Port Steward, had provisioned the supertanker on her departure from Kure with the finest Australian beef and mutton, fresh fish, vegetables, fruits and many other delicacies.

The food was good, he was a great “feeder”. Officially, only the

two Captains and the Chief Engineer had right to alcoholic beverages, “as amenities to visiting shore-side authorities”. Some of us kept a few cases of beer and

a few bottles of other "supplies" in our quarters. There was an unwritten policy of tolerance aboard. As long as we behaved ourselves and did our job, Captain McGuire

closed his eyes. The seating arrangements in the Officer’s saloon was in accordance with traditional European Merchant

Vessel’s customs: The two Captains, Chief Engineer, Chief Mate and 1st Assistant Engineer ate separately in a smaller

dining lounge adjoining the main officer’s mess. We did not wear any uniforms,

but Captain McGuire did not tolerate T-shirts and insisted that we always wear clean shirts and shoes at dinner time.

The close friendship between Chief

Engineer John Rawles and Captain Mc Guire dated back to the war. They had sailed together on the North

Atlantic convoys.. Rawles was a very nice person and we became good friends. His hobby was photography; he was also a radio amateur. Twice daily, he

came forward to the mid-ship house to “report to the captain”, his arrival coinciding with the cocktail hour. Passing near the radio room, he called

in : ”Spark’s, setup your chess board.”. When he came down

from the Captain’s deck, he stepped into the radio room and, not bothering to sit down, made me “check mate”

in three or four moves. It went so fast that

I had no time to remember his moves. The second mate was a Norwegian who

had lived in Australia during the war.

He had an horrible accent. One of his many swear words was ”Bleuidy...”. I could not tell if he was speaking English

with his Norwegian accent and an Australian pronunciation, or the other way around.

The third mate was from New Zealand,

built like a rugby player. He was a cheerful fellow. His stateroom was across the alley way from the radio room. Sometimes,

he would step out of the shower bare a… naked but covered with soap lather from head to toe and call out to me: “Sparks, take my photograph...” (to send to his girl friend?).

He became another of the many friends I had on board.

PART FOUR

THE LONG VOYAGE

On the eve of our arrival off the Golden Gate there was a big poker game with Captains Jesse Bird and McGuire, John Rawles,

Chief Mate Baum, and a few others in the Captain’s quarters. I have never been interested in any card games nor do I

gamble. I spent the evening taking care of the radio station’s accounts and checking all the ship’s paperwork

for clearing her into port the next day. Early in the morning, we passed under the Golden

Gate Bridge. I have not recorded the number of times

I passed under it aboard a ship, from 1955 to this date. At each of my passages, in

- or outbound, I always feel an indescribable emotion, like a pure joy.

A gigantic reception committee of tug boats, launches, helicopters and private planes

with newspaper reporters and photographers attended our arrival. We dropped our anchors at the quarantine station between

the Ferry Building and Alcatraz Island. While old Jesse Bird hosted

the different company executives and higher authorities with his liquid (!) gratuities, I assisted Capt. McGuire with the

ship’s clearance and crew payoff. Joseph Baum, the Chief Mate, did not measure up to old Jesse’s standards; he

was discharged and replaced by Capt. Daniel Haff, who, later would start a new career as a brilliant Panama

Canal pilot. He was a very nice person, and we became good friends. On

the first evening after our arrival, the same “band of brothers”: Joe Baum the Chief Mate, the 3rd Mate, 3rd Engineer,

Steward, the last three from Hamburg and Bremen, and the Radio Officer (myself), who

had made the last rounds of Kure’s bars the night before our departure, went ashore with a crew launch. We were disagreeably

surprised to find a few customs agents in civilian clothes awaiting us on the pier. They frisked us for narcotics and other

supposed contraband. But we were clean, and they became friendly. After a good steak diner, we left some of our hard earned

Dollars at a few “bistros” between Union Square

and Geary Street.

When we sailed from Mena Al Ahmadi, the Esso Lorraine

sounded her steam whistle in salute to the Universe Leader, all her officers

and crew lined the rails to cheer us along with their most cordial “Bon voyage, good bye, bonne chance, au revoir”. There was no ceremony when the Universe

Leader crossed the Equator. It was my first “crossing of the Line”.

But thanks to the several cases of good wine Captain McGuire had bought from the French tanker, our Christmas and New Year’s

parties were memorable affairs. I saw my first albatrosses when we went around

the Cape of Good Hope to enter the South Atlantic bound for Santos, Brazil.

The Suez Canal was still closed. All maritime traffic bound for Europe and the Americas, all

ships coming from the West sailing to the Persian Gulf and beyond to Asia had to go around the Cape of Good Hope, and called

at Cape Town for bunkers, provisions and mail.

In 1957, the Universe Leader, the largest tanker in the World, was due for her

first dry-dock period. Only a few shipyards worldwide were able to accommodate her: Kure, in

Japan, Vancouver in British

Columbia, Casilias near Lisbon and Capetown,

South Africa.

Departing from Santos we crossed the Atlantic in good

weather conditions, bound for this Southern most city of the African Continent. On a beautiful day of February 1957, the Universe

Leader’s arrival was the main event and made the front-page of every newspaper in South Africa. Planes and small craft of all sizes, crowded with newspaper reporters

and photographers, where all over and around us when we entered port. The harbor was packed with tankers, freighters, and

passenger ships. As usual I assisted Captain McGuire with the vessel’s clearance, while Chief Mate Haff and Chief Engineer

Rawles were busy with shipyard engineers. As soon as I stepped ashore I became aware of the strict regulations imposed on

the people of South Africa separating

colors of skins and races. I wondered how our crew of West Indians and Japanese would be treated. But I was too young and

certainly too selfish to worry about all those things. I could not solve by myself all the world’s problems. The city

was beautiful. At the foot of the magnificent Table Mountain, in the town’s center, tall modern buildings, bordered her large avenues.

While enjoying a glass of excellent “Cape Colony” wine at the bar of the largest hotel, I heard two ladies near me conversing

in French. I got up and very politely, in French, apologized for speaking to them. I explained my reason for being in Cape Town. The ladies were very friendly and soon we shared an excellent

lunch. The elderly lady expected her husband to arrive that day with their car aboard the Dutch passenger liner SS Bloemfontein.

The very pretty younger one, Olga Rausch, was their secretary. They had just

returned from a holiday back home in Belgium and intended to travel by

car, through the heart of Africa back to Usumburu, capital city of the Belgian colony of Ruanda - Burundi where they owned a big garage. What a safari! I wished I could make that

voyage with them! This was before the Belgian Congo’s independence. Great Britain, France and Belgium still shared most of Africa among them and traveling

through the continent was quite safe at that time. The next day, my new friends took me up to the summit of Table Mountain in their car before leaving

for their long journey. A group of the famous Follies Bergères

Music Hall from Paris was passing through Cape Town on a world tour.

That evening I went to their show, and talked afterward back stage with the artists'. The next day, the Universe Leader entered into dry dock. I took a sight- .seeing tour by bus to Cape Agulhas,

the real Cape of Good Hope, where we saw baboons

in the wild. The South African country side was beautiful and reminded me of the South of France. There were fertile fields,

vineyards, green hills, blooming trees. I noticed among my fellow passengers (naturally all white) an elderly gentleman and a young lady. They were Italians, father

and daughter from La Brescia, on a business trip to South Africa.

They spoke good French. We were able to exchange our impressions and became friends.

On my return to Cape

Town, after dinner, I sampled the local brew in a large beer hall full of noisy sailors. A brass band

playing popular tunes added to the high noise level of the place. At one time, I witnessed a developing conflict between British

and Scandinavian seamen. Rapidly the exchange of insults degenerated in a general fight; fists, then beer glasses and bottles

began to fly through the air, blood erupted from squashed noses. I am of a peaceful

nature, allergic to violence, and have always avoided such brawls in public places. I was lucky to be near the exit. I had already paid for my beer and could escape the "battlefield" unobserved and without

harm. I joined my Captain and the ship’s staff in a nightclub where soon

I met a friendly lady who gave me a warm shelter... (and all the rest) for a merry night of love.. The next morning I wanted

to go aboard my ship for a shave and a change of clothing. There were hundreds of sightseers watching her being towed out

of the floating dry-dock. I recognized my two Italian friends from the day before who introduced me to their hosts. They were

Maltese. The gentleman was the general manager of a large bank in Cape Town.

They invited me to their home, a beautiful residence on the outskirts of the city, close to a beach of sparkling white sand

and treated me to a delicious lunch. Afterwards, they loaned me a pair of swimming trunks for a dip in the warm waters of

the Indian Ocean. We spoke French the whole time; they were charming hosts, very cultivated

and I promised myself I would learn Italian in the coming months. They brought me back to port that same evening. I took them

aboard the Universe Leader and afterwards we visited an Italian passenger ship moored on the same pier. When I returned

to Japan the following summer, I sent

them a beautiful Japanese doll, in memory of their warm hospitality. For a few

years I exchanged postcards with my new friends from Cape Town

and with Olga Rausch from Usumburu. She wrote me of her engagement to a flight engineer of Sabena, the Belgian airline. I

often have asked myself what had become of her and her friends during the big mess and the many conflicts, after Belgium was

forced to give independence to the Congo and her other colonies.

A few artists of the Follies Bergères visited the Universe

Leader while she was in dry-dock and one of the acrobats, while performing a hand stand on the prow had her photograph

taken by a local newspaper reporter.. It was good public relation for our ship.

During the few days of our stay in Cape

Town, our unlicensed crew members had been well taken care off by the other ethnic communities of South Africa. All of us brought along many pleasant memories

of this beautiful port. Rarely have I seen elsewhere sailors being so welcome as

in Cape Town in February of 1957.

We sailed

across the Indian Ocean bound for Sungai Pakning, to load crude oil for San Francisco.

We headed directly for the Northern entrance of the Strait of Malacca, passing near the Island of Mauritius. We all were getting a

little tired of this long voyage, afflicted with the traditional ailment of "Tankeritis".

We longed for mail, for news from home, for a change of scenery. It was a long track

across the treacherous monsoon waters of the Indian Ocean....

I love long sea passages. But when my supply of unread books and magazines is depleted, when I have to read for the

second or third time all the reading material of my sea-borne library and when as a last resort I have to raid the officer’s

and unlicensed lounges to find only frayed pocket books of Westerns or mysteries, the situation reaches a critical stage!

We stayed

five to six days at Sungai Pakning until the river tankers had brought enough crude oil down from the oil fields up-river

to fill our ship. Again I met my Dutch friends and enjoyed agreeable afternoons and evenings sipping numerous bottles of Heineken

beer, lunches and dinners at the club of delicious curry and other Indonesian dishes.

At last were bound for San

Francisco. We crossed the International Date Line from East to West, which gave us an extra day on

our calendar. We encountered some Pacific squalls and gales, and were about three days out from San Francisco when John Rawles came into my radio room one afternoon. He asked me to type